Introduction

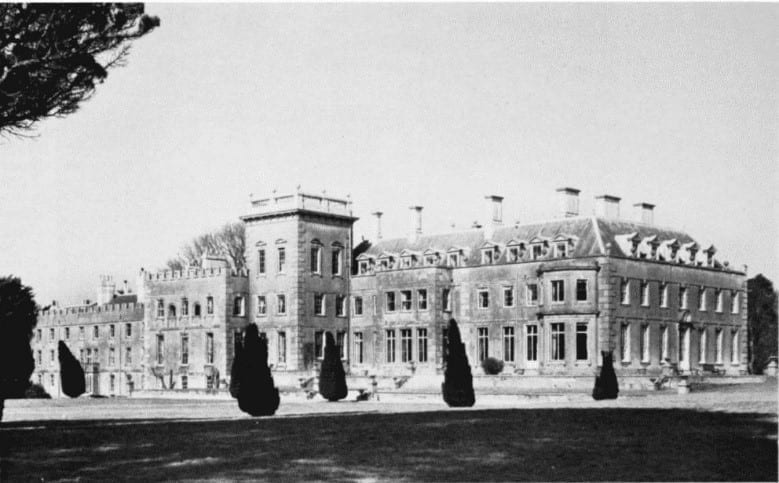

Anthony Ashley-Cooper was born on April 28, 1801 in Mayfair, London, into wealth and privilege. Being the eldest son, of nine children, on the death of his father, he would become the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury and inherit his father’s peerage and large estate including St Giles House Dorset (shown), until then he was referred to as Lord Ashley. However, as a landholder with a small income and benevolent impulses, Shaftesbury existed in a chronic state of debt. On the death of his father, he inherited an estate which required much renovation and maintenance, as well as significant debt.

Anthony Ashley-Cooper was born on April 28, 1801 in Mayfair, London, into wealth and privilege. Being the eldest son, of nine children, on the death of his father, he would become the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury and inherit his father’s peerage and large estate including St Giles House Dorset (shown), until then he was referred to as Lord Ashley. However, as a landholder with a small income and benevolent impulses, Shaftesbury existed in a chronic state of debt. On the death of his father, he inherited an estate which required much renovation and maintenance, as well as significant debt.

Both his parents were distant from him and he suffered from the lack of their affection. In his early years one of the house staff, Maria Millis, a committed Christian, showed him genuine love, read Bible stories to him and taught him to pray. This became the pattern for his life and the central driving force of all his thoughts and actions. Maria died when Anthony was only eight, but a seed had been sown, and his  course for life had been set.

course for life had been set.

He married Lady Emily (his Emmy) daughter of the 5th Earl Cowper in 1830. They had ten children, four died during Ashley’s lifetime, and their marriage was one of mutual affection from beginning to end. Ashley suffered from periodic bouts of depression which he shared with other notables such as the Prince of Preachers, Charles Haddon Spurgeon and Winston Churchill’s fits of depression, he called his “Black Dog.”

In 1826, Lord Ashley entered politics as a conservative member of parliament and from there he commenced his life-long battle for the destitute, abused, helpless, defenceless and rejected members of society. At times he thought that he was alone in his campaign and at other times he thought that everybody was against him. However, his reforms lifted the lives of thousands, starting with changing the lunacy laws under which, poor crazed people were subject to institutionalised cruelty. Next came his campaign to reduce the working hours of factory children who were under the age of thirteen to ten hours. Then legislation to prevent boys and girls as young as five working in the pitch black and filth of underground coal mines. Also for young boy chimney sweeps who were being forced to climb up the inside of chimneys with the resultant effect on their health, the expansion of the Ragged Schools for little illiterates, as well as his Public Health laws. Shaftesbury, as he later became, put his Christian faith into action.

Shaftesbury kept a diary for most of his life[1] therefore it was a much easier matter for Edwin Hodder, whom Shaftesbury chose at the end of his life, to compose his biography. As well, Hodder had access to a large collection of public and private correspondences. His biographical work consists of a three-volume set and it was published in 1887. In 1923 J L and Barbara Hammond published a book detailing the significant contribution Shaftesbury made to the politics and history of his age. In 1964 Geoffrey Best published a book showing the reforms that Shaftesbury had made. In 1975, Georgina Battiscombe published her book titled, Shaftesbury The Great Reformer[2]and it is from this book that most of this article has been taken.

Shaftesbury’s reforms

Lunacy Laws

One year after entering politics, Lord Ashley was appointed to the Select Committee on Pauper Lunatics. In this capacity, he toured the madhouses around London and found, patients chained up and sleeping naked on straw. All their excrement went into their straw beds which was only changed weekly and at that time the patients were washed with cold water. One towel was allotted to be shared by 160 people and no soap was provided. The treatment of “crib cases’ at the madhouses of Bethnal Green is described by Richard Roberts , assistant to the Overseers of the Poor thus: as a place where there is nothing but wooden cribs filled with straw and covered by a blanket in which these unfortunate beings are placed at night and they sleep most of them naked on straw and of course do all their occasions in their cribs. Another witness said; they were chained by hand and feet and if they were to get up in a great state of fury, they might dislocate their wrists and ankles.[3]

As a result of Ashley’s investigations and continual agitations, laws were instituted in 1828 that relieved the suffering of the lunatics greatly. However, more needed to be done and during a masterful speech to parliament in 1845, he cited the plight of a Welsh lunatic girl, Mary Jones, who had been shut up for more than ten years in a tiny loft with one boarded-up window which admitted little air and no light. The room was indescribably filthy and the smell almost intolerable; the miserable girl could only squat in a bent and crouching posture, which had produced shocking deformity and her countenance, still pleasing, was piercingly anxious and marked by an expression of despair.[4] In July 1845, two much more important Bills became law; Ashley’s great Lunacy Acts, For the Regulation of Lunatics Asylums and For the Better Care and Treatment of Lunatics in England Wales.

His battle for the plight of lunatics lasted all of his life.

The Ten-Hour Bill

As steam replaced water for the powering of machines, industries moved from streams to towns where the supply of child labour was plentiful. A lot were pauper apprentices who were herded together in bleak, insanitary factory “barracks.” Children as young as five years old worked in the factories for twelve-hour days and often for fourteen and even sixteen hours. Not infrequently, they worked all through the night. Some were caught in unfenced machinery and suffered terrible injuries; many were crippled by the nature of the work they were made to perform; others fell victim to the various forms of tuberculosis caused by the unhealthy, dirt-laden atmosphere of the mills. They snatched their food as they worked, because during the official meal-breaks they had to clean the machinery. Hungry and exhausted towards the end of the day, they fell asleep at their work and could only be aroused by blows from the overseer’s whip. They had no time free for school and at work they learnt no skills which could be of use to them in later life.[5]

In March 1833 Ashley introduced the Ten Hours Act 1833 into the Commons, which provided that children working in the cotton and woollen industries must be aged nine or above; no person under the age of eighteen was to work more than ten hours a day or eight hours on Saturday. This Bill was amended, defeated, and finally in January of 1847, it became law and known as the Ten Hours Act.[6]

Unfortunately, mill owners found a way of circumventing the Bill by way of a roster system and in order to block this loophole Ashley had to compromise to ten- and one-half hours which finally became law in August 1850, seventeen years after its first introduction.[7]

Climbing Boys (Chimney Sweeps).

Young boys were forced and at times screaming and sobbing, to climb chimneys, their skin scorched and lacerated, their eyes and throats filled with soot, Ashley found a child of four and a half working as a climbing boy. These small boys faced suffocation in the blackness of a chimney, or perhaps a slow and painful death from cancer of the scrotum, the climbing boys’ occupational disease.[8] Of all unhappy child workers these were perhaps the most ill-used and forlorn.

Young boys were forced and at times screaming and sobbing, to climb chimneys, their skin scorched and lacerated, their eyes and throats filled with soot, Ashley found a child of four and a half working as a climbing boy. These small boys faced suffocation in the blackness of a chimney, or perhaps a slow and painful death from cancer of the scrotum, the climbing boys’ occupational disease.[8] Of all unhappy child workers these were perhaps the most ill-used and forlorn.

In 1847 a terrible case occurred in Manchester where a little seven-year-old boy was forced up a hot flu, pulled out half suffocated, and then cruelly beaten. The child later died in convulsions. This and other similar cases led to the foundation of the Climbing-Boys Society, with Ashley as chairman. It called for the total abolition of the scandal. In 1851, 1853 and 1855, he introduced Chimney Sweeps bills into parliament, but in spite of the shocking evidence, all these bills were defeated. In 1864 he succeeded in passing through both houses yet another act to forbid the use of climbing-boys; but like all its predecessors, this measure remained almost totally ineffectual. Finally, after two more deaths of boys in flus, in 1875 he introduced a bill which prescribed the annual licencing of chimney sweeps, once again prohibiting the use of climbing-boys and gave the enforcement of the law into the hands of the police, a measure which proved powerful enough finally to put an end to the scandal.[9]

Many of the boys used as chimney sweeps were the illegitimate children of prostitutes who sold their children to wicked masters.

Children working in coal mines

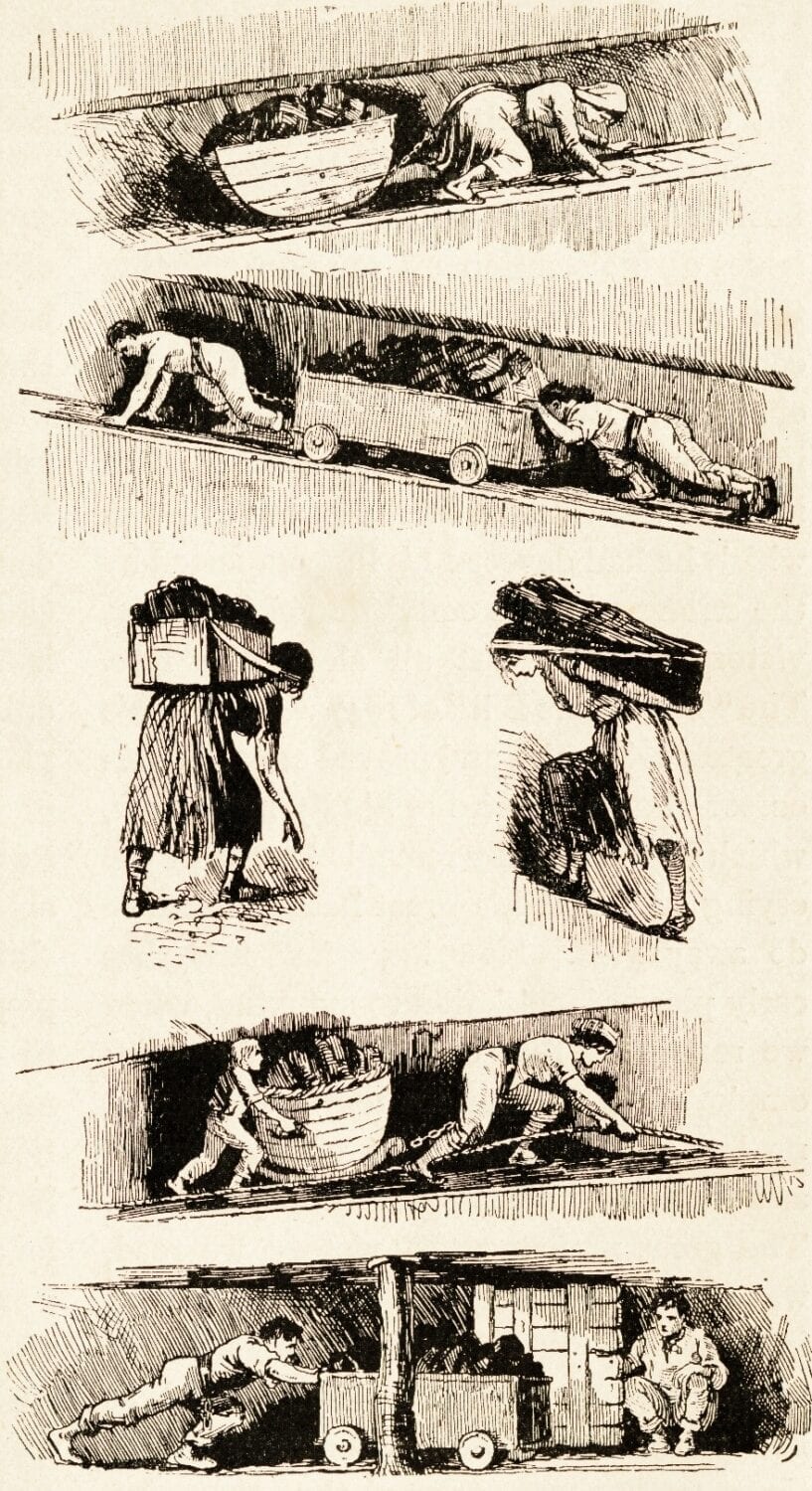

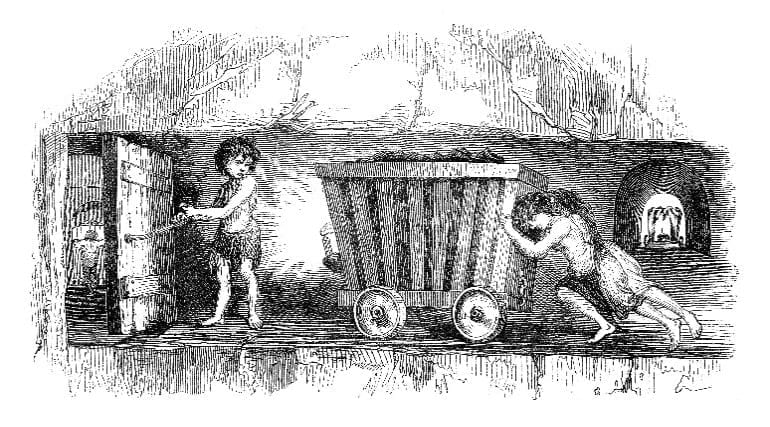

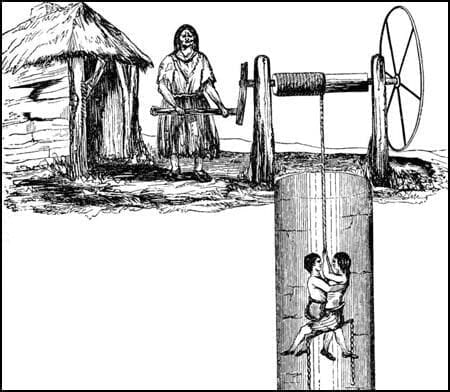

In order to bring to public attention, the conditions under which children and women worked in coal mines, Dr Thomas Southward-Smith had an illustrator construct a series of images which were then

disseminated to the public. Some are presented here. The drawings showed little children carrying huge baskets of coal up long steep ladders, small five or six year old ‘trappers’ sitting alone in the darkness opening and shutting ventilation doors, and most horrific of all, a woman or child harnessed to a truck by a chain passed between his/her legs and fastened to a heavy girdle, crawling on all fours to pull loads of coal through passages eighteen inches (450 mm) to two feet (600 mm) high. Ashley’s contemporaries were more shocked by a drawing of a half-naked boy and girl sitting face to face astride a bar, she holding the rope, he with his arms around her body, whilst a decrepit old woman turned the hand windlass which lowered them down the shaft.[10]

disseminated to the public. Some are presented here. The drawings showed little children carrying huge baskets of coal up long steep ladders, small five or six year old ‘trappers’ sitting alone in the darkness opening and shutting ventilation doors, and most horrific of all, a woman or child harnessed to a truck by a chain passed between his/her legs and fastened to a heavy girdle, crawling on all fours to pull loads of coal through passages eighteen inches (450 mm) to two feet (600 mm) high. Ashley’s contemporaries were more shocked by a drawing of a half-naked boy and girl sitting face to face astride a bar, she holding the rope, he with his arms around her body, whilst a decrepit old woman turned the hand windlass which lowered them down the shaft.[10]

Ashley introduced the Miners and Collieries Act of 1842 which prohibited the employment of women and children in underground coal mines. He spoke in support of the Act and Prince Albert wrote to him congratulating him warmly and concluding with; best wishes for your total success. Ashley’s Mines Act of 1842 was described by the Hammonds[11] as the most striking of his personal achievements.[12]

Education for Poor children

The Ragged Schools[13], as they became to be known, sprang up whenever or wherever two or three devoted enthusiasts set to meet an obvious need. For example, Miss Charlotte Yonge described how a fifteen-year-old girl started such a school in a neglected hamlet for children too dirty and ragged to go to the neighbouring National School. Ashley calculated that a school for 280 children, open every evening, could be run on £58 per year.

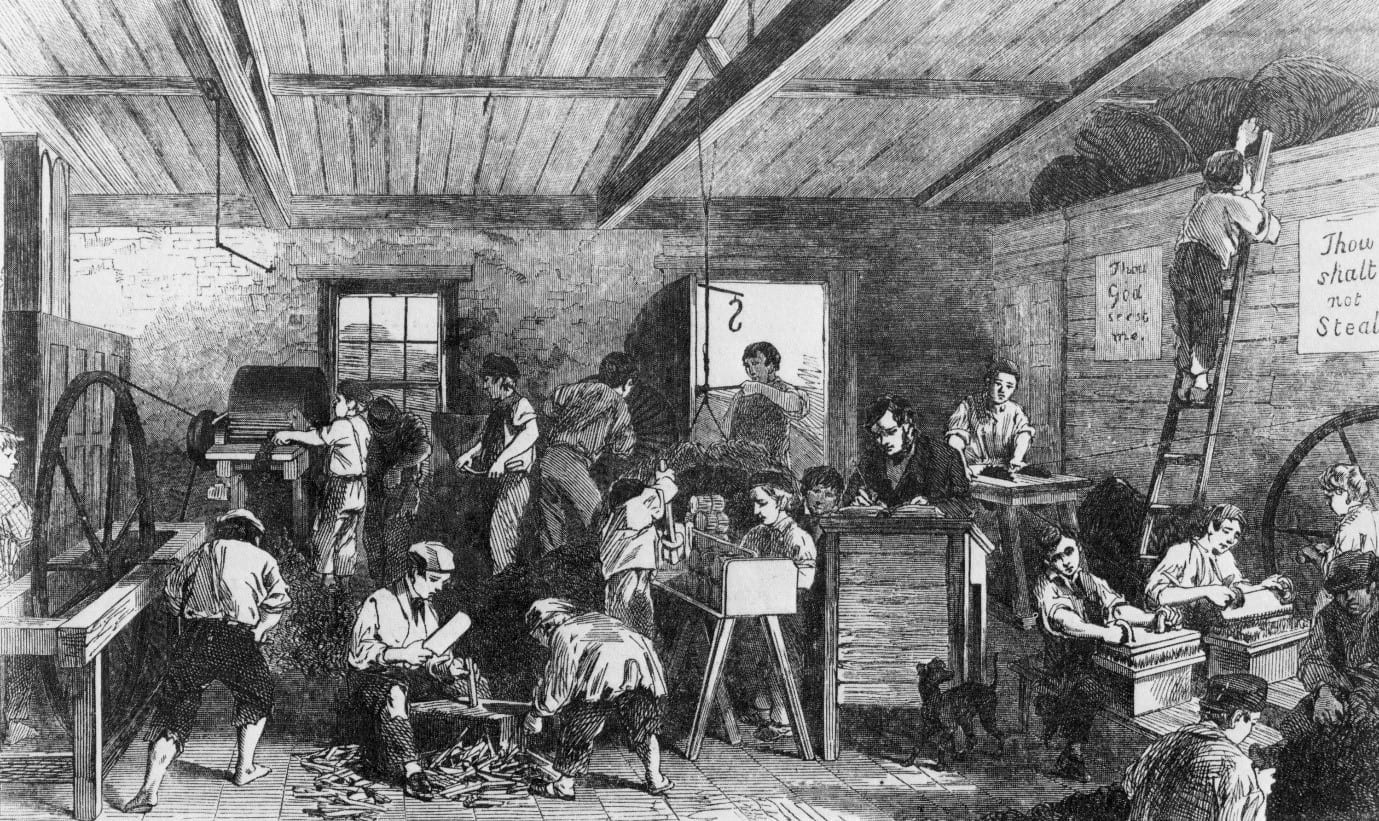

In April 1844 four men of meagre means met to form an association ‘to give permanence, regularity and vigour to existing Ragged Schools and to promote the formation of new ones throughout the Metropolis,’ From that resolution came the Ragged Schools Union with Lord Ashley as its president. The schools  were places where, to quote the Hammonds,[14] these outcast children ‘had learned their Bibles, had come to like clean faces and clean collars, had grown into respectable and God-fearing men and women. The schools also taught the three Rs, and sometimes gave them the rudiments of training in a handicraft.[15]

were places where, to quote the Hammonds,[14] these outcast children ‘had learned their Bibles, had come to like clean faces and clean collars, had grown into respectable and God-fearing men and women. The schools also taught the three Rs, and sometimes gave them the rudiments of training in a handicraft.[15]

Ashley’s passionate preoccupation with Ragged Schools caused him to state in his old age, If the Ragged School system were to fail, I should not die in the course of nature, I should die of a broken heart.

The sketch is of the Ragged School in Brook Street, London in 1853.

The Board of Health

The man who played the chief part in exposing the scandal of the appalling sanitary conditions existing all over the British Isles was Edwin Chadwick. He drafted the 1842 Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. The report resulted in the establishment of the Board of Health of which Ashley was a very active member from 1848 to 1854. In 1848 a cholera epidemic broke out. At its height in September 1849, 2,298 people died in one week. In 1848, London’s water, both for washing and drinking, was drawn from the Thames, a river which also received the whole of London’s sewage. Despite the efforts of the Board by as late as 1886, Londoners were still drinking Thames water.

The concrete result of Ashley’s six years work was small indeed. A few insanitary areas had been cleaned, a few local schemes for drainage and water supply set in motion; all large plans and reforms had come to nothing. Yet those six years were emphatically not wasted. For the very first time a statutory body had assumed control for such affairs; the very first time politicians and people alike had been brought to acknowledge that public health was of public concern.[16]

Ancillary Work

Jewish Homeland

As a pre-millennial evangelical Christian, Ashley believed that the Jews needed to return to their homeland before the Second Advent could come about and he did all that was in his power for Britain to secure that homeland.[17]

Opium Trade

In 1843 Ashley expressed his indignation of Britain’s Foreign Policy: that for reasons of trade and revenue, the British should force a foreign power to open its ports to the opium traffic, as it does to posterity, a gross immoral act, more black, more cruel, more satanic than all the deeds of private sin in personal history.

Shaftesbury served as the first president of the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade from 1880 until his death.[18]

Schools teaching Seamanship

Both the Royal Navy and the Merchant Services were finding difficulty in manning ships at a time when hundreds of lads were running wild about London’s streets. Meanwhile, disused, but still serviceable vessels were cluttering up the Admiralty yards. Shaftesbury conceived the idea of fitting out one of these old ships, filling it with boys of the Ragged School type, and training them for a sea-going life. In 1866, 150 homeless boys were collected and the education and training commenced. Within six years other ships were fitted out and hundreds of boys were removed from the streets and given a future as seamen.[19]

Shaftesbury’s Death

It was October 1, 1885 with the autumn sun filling the room and his children gathered around him, Shaftesbury died very quietly. He had always dreaded death in the dark.

It was October 1, 1885 with the autumn sun filling the room and his children gathered around him, Shaftesbury died very quietly. He had always dreaded death in the dark.

In accordance with his own wish, he was buried at St Giles, although he was offered a crypt at Westminster Abbey. However, the nation was determined to honour him with a funeral service at Westminster Abbey. From early morning on October 8, the pavement along the route between Grosvenor Square and Westminster were thronged with poor people, costermongers, flower girls, boot blacks, crossing-sweepers, factory hands and the like waiting patiently for hours in order to catch a brief sight of the coffin as it passed, showing their love and gratitude for the man who championed their cause.[20]

Summary

The force that drove Shaftesbury was a passionate concern for souls. He believed that factory children, chimney sweeps and lunatics all had souls to be saved and that very little time remained in which to save them. “It is eternity work,” said a Welsh Evangelical on his death-bed; men like Wilberforce and Ashley and, indeed the Evangelicals as a whole, saw all social and charitable efforts as “Eternity work.”[21]

Charles Haddon Spurgeon summarised Shaftesbury’s life adequately with:

During the past week the church of God, and the world at large, have sustained a very serious loss. In the taking home to himself by our gracious Lord of the Earl of Shaftesbury, we have, in my judgment, lost the best man of the age. I do not know whom I should place second, but I certainly should put him first—far beyond all other servants of God within my knowledge—for usefulness and influence. He was a man most true in his personal piety, as I know from having enjoyed his private friendship; a man most firm in his faith in the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ; a man intensely active in the cause of God and truth. Take him whichever way you please, he was admirable: he was faithful to God in all his house, fulfilling both the first and second commands of the law in fervent love to God, and hearty love to man. He occupied his high position with singleness of purpose and immovable steadfastness: where shall we find his equal? If it is not possible that he was absolutely perfect, it is equally impossible for me to mention a single fault; for I saw none. He exhibited scriptural perfection, inasmuch as he was sincere, true, and consecrated. Those things which have been regarded as faults by the loose thinkers of this age are prime virtues in my esteem. They called him narrow; and in this they bear unconscious testimony to his loyalty to truth. I rejoiced greatly in his integrity, his fearlessness, his adherence to principle, in a day when revelation is questioned, the gospel explained away, and human thought set up as the idol of the hour. He felt that there was a vital and eternal difference between truth and error; consequently, he did not act or talk as if there was much to be said on either side, and, therefore, no one could be quite sure. We shall not know for many a year how much we miss in missing him; how great an anchor he was to this drifting generation, and how great a stimulus he was to every movement for the benefit of the poor. Both man and beast may unite in mourning him: he was the friend of every living thing. He lived for the oppressed; he lived for London; he lived for the nation; he lived still more for God. He has finished his course; and though we do not lay him to sleep in the grave with the sorrow of those that have no hope, yet we cannot but mourn that a great man and a prince has fallen this day in Israel. Surely, the righteous are taken away from the evil to come, and we are left to struggle on under increasing difficulties.[22]

Acknowledgements

The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury is from wikimedia commons

Chimney sweeps; http://www.cypruschimneysweeps.com/411623083

Sketches were purchased from Istock photos and Alamy Stock photos

[1] It is clear from his writings that he had every intention of destroying them before his death.

[2] Georgina Battiscombe, Shaftesbury The Great Reformer 1801-1885, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1975.

[3] Battiscombe, page 36.

[4] Battiscombe, page 182.

[5] Battiscombe, page 69-70.

[6] Battiscombe, page 202.

[7] Battiscombe, page 212.

[8] Soot contains a group of carcinogenic (cancer producing) compounds know as Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs).

[9] Battiscombe, page 126-127.

[10] Battiscombe, page 146.

[11] Battiscombe, page 146

[12] Battiscombe, page 148.

[13] The adjective ‘ragged’ was chosen of set purpose, not as an insult, but as an encouragement to the type of children for whom theses schools were intended.

[14] In 1923 J L Hammond and Barbara Hammond published a book whose aim was to describe Shaftesbury’s life and character and the significant contribution which he made to the politics and history of his age.

[15] Battiscombe, page 194-196.

[16] Battiscombe, page 119-134.

[17] Battiscombe, page 100.

[18] Battiscombe, page 155.

[19] Battiscombe, page 291.

[20] Battiscombe, page 332.

[21] Battiscombe, page 102.

[22] Departed Saints Yet Living. The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons. Vol. 31. London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1885. 541–542.