Introduction

As papyrus and parchment gradually replaced clay tablets, bullae (bulla, plural, also called seals) became the new encasement for scrolls of this new writing style. Documents were split into two halves, separated in the middle by multiple perforations. The top half was rolled into a scroll and a cord would wrap this section tight, going through the perforations. Clay was impressed on the cord to avoid unauthorized reading and the bottom of the document was then wrapped around the initial scroll. The complex method of sealing was to prevent a scroll from simply being pulled out from the seal. Seals were used as well, in pottery to authenticate the manufacturer.

The use of seals to authenticate a document is mentioned in the Bible:

1 Kings 21:8 referring to Jezebel; So she wrote letters in Ahab’s name and sealed them with his seal and sent letters to the elders and to the nobles who were living with Naboth in his city.

Daniel 6:17; A stone was brought and laid over the mouth of the den; and the king sealed it with his own signet ring and with the signet rings of his nobles, so that nothing would be changed in regard to Daniel.

When a city was destroyed by fire, the scrolls would be burnt, but the clay seals would only become harder and more durable. Many have been found in archaeological sites, especially when wet washing was used.

Isaiah’s seal

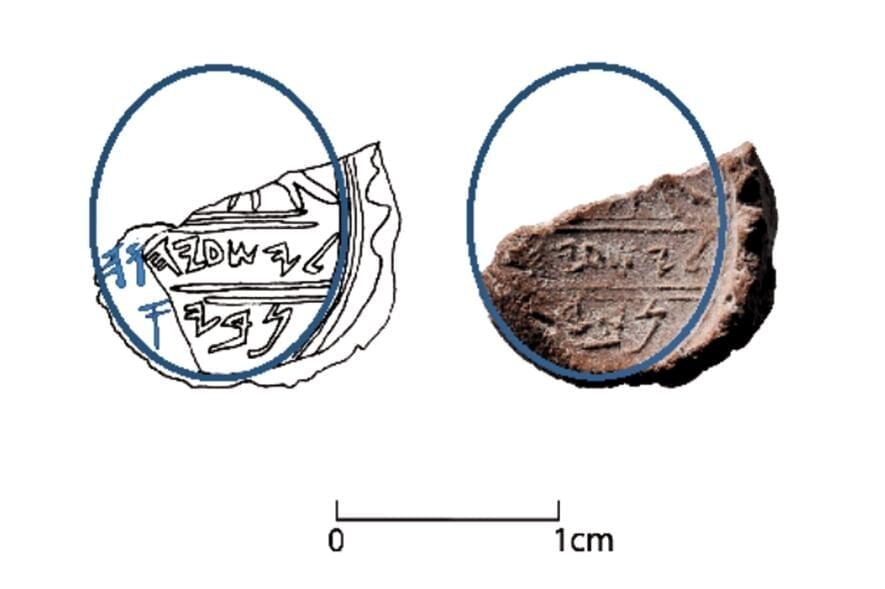

Archaeologist Eilat Mazar has announced recently, in Biblical Archaeology Review[1], that she may have discovered the bullae (seal) of Isaiah the prophet who lived at the time and was a contemporary and advisor to king Hezekiah during excavations of the Ophel site immediately south of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. If this is the case, it will be the only mention of Isaiah from outside the Bible. The reason for the uncertainty, is that what was found was only half the seal and as Eilat explained: The seal is impressed in Old Hebrew script with the name Yesha‘yah[u] (the Hebrew name of Isaiah), followed by the word nvy. Because the seal is damaged at the end of the word nvy, Mazar suggests that our reading may be incomplete. If nvy was originally followed by the Hebrew letter aleph, the result would be the word “prophet,” rendering the reading of the seal as “Belonging to Isaiah the prophet.”

the uncertainty, is that what was found was only half the seal and as Eilat explained: The seal is impressed in Old Hebrew script with the name Yesha‘yah[u] (the Hebrew name of Isaiah), followed by the word nvy. Because the seal is damaged at the end of the word nvy, Mazar suggests that our reading may be incomplete. If nvy was originally followed by the Hebrew letter aleph, the result would be the word “prophet,” rendering the reading of the seal as “Belonging to Isaiah the prophet.”

As tempting as the interpretation may be, Mazar concedes there are “major obstacles” in the identification of the seal, most notably the word nvy. Without an aleph at the end, nvy is probably just a personal name (often the name of the person’s father) or a location (where the person hails from).

Christopher Rollston, professor of Semitic languages at George Washington University, agrees that the reading of nvy is a problem. Compounding the reading of nvy is a lack of the definite article “h”, notes Rollston. In the majority of biblical references, references are to “the prophet” rather than simply “prophet.” “In short, if this were the word ‘prophet,’ I would have liked to have seen the word ‘the,’ as in ‘Isaiah the prophet,’ he says. While Mazar notes that the lack of definite article is also a problem in interpreting the seal, she includes a suggestion that the definite article may have originally appeared in a damaged area above the word nvy, or, citing other archaeological and textual examples, was simply left out.[2]

Christopher Rollston, professor of Semitic languages at George Washington University, agrees that the reading of nvy is a problem. Compounding the reading of nvy is a lack of the definite article “h”, notes Rollston. In the majority of biblical references, references are to “the prophet” rather than simply “prophet.” “In short, if this were the word ‘prophet,’ I would have liked to have seen the word ‘the,’ as in ‘Isaiah the prophet,’ he says. While Mazar notes that the lack of definite article is also a problem in interpreting the seal, she includes a suggestion that the definite article may have originally appeared in a damaged area above the word nvy, or, citing other archaeological and textual examples, was simply left out.[2]

Conclusion

There are several points to consider regarding this find:

1 The seal was found during a supervised archaeological dig. It was not purchased on the antiquities market as some have been.

2 It was found in the same area where other significant seals have been found, e.g. Hezekiah and Jeramiah’s jailers. For more on this go to: adefenceofthebible.com/2016/01/02/hezekiahs-seal-found.

3 The other significant seals found at the site were of the same period; the reign of Hezekiah and the events leading to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BC.

4 The name of Isaiah is clear and undisputed and as shown above in the schematic, there is room for the Hebrew letters to render the inscription; “Belonging to Isaiah the prophet.”

It is tempting to speculate that if the seal is authentic as is quite possible, did it protect some document that Isaiah wrote which we have in our Bible?

[1] Biblical Archaeology Review, vol 44, 2&3, 2018, pages 64-73.

[2] news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/02/prophet-isaiah-jerusalem-seal-archaeology-bible.