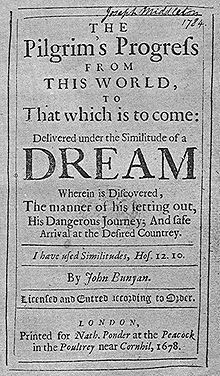

It has been claimed to be the greatest selling book of all time apart from the Bible of course.[1] Although it is difficult to amass numbers to validate such a statement, but there is no doubt that if it is not the greatest selling book, it must be close to it. The Pilgrim’s Progress, full name, The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to That Which Is to Come, was written by John Bunyon and first published in 1678 with a second part added in 1684. It has been translated into more than 200 languages and has never been out of print in almost 350 years. According to literary editor Robert McCrum, there’s no book in English, apart from the Bible to equal Bunyan’s masterpiece for the range of its readership, or its influence on writers as diverse as William Hogarth, C. S. Lewis, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Louisa May Alcott, George Bernard Shaw, William Thackeray, Charlotte Bronte, Mark Twain, John Steinbeck and Enid Blyton.[2]

It has been claimed to be the greatest selling book of all time apart from the Bible of course.[1] Although it is difficult to amass numbers to validate such a statement, but there is no doubt that if it is not the greatest selling book, it must be close to it. The Pilgrim’s Progress, full name, The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to That Which Is to Come, was written by John Bunyon and first published in 1678 with a second part added in 1684. It has been translated into more than 200 languages and has never been out of print in almost 350 years. According to literary editor Robert McCrum, there’s no book in English, apart from the Bible to equal Bunyan’s masterpiece for the range of its readership, or its influence on writers as diverse as William Hogarth, C. S. Lewis, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Louisa May Alcott, George Bernard Shaw, William Thackeray, Charlotte Bronte, Mark Twain, John Steinbeck and Enid Blyton.[2]

It is not just the ancient English who loved it, when China’s Communist government printed The Pilgrim’s Progress as an example of Western cultural heritage, an initial printing of 200,000 copies was sold out in three days![3] In fact, the Chinese translations made the book one of the most popular translated novels in China between the late 19th and the early 20th century. First published in Classical Chinese in 1851 and then in Mandarin and different Chinese dialects after 1865 and 1871.

John Bunyan

John Bunyan was born in Elstow in November of 1628. His family were tinkers, members of a craft that used the heat of a brazier to repair or make metallic utensils in England’s agricultural Midlands. He learnt to read and write at a local grammar school. When he died in August 1688, he had lived through a period of great political, social, and religious change in England. While he was still a boy, tensions between King Charles I and Parliament erupted into a bloody civil war which led to the defeat and execution of the king, and the establishment of a republic under Oliver Cromwell. Even though the monarchy was restored under Charles II in 1660, England had been transformed from where the king aspired to absolute rule, to one where Parliament had gained political power.

Bunyan served as a soldier in the Parliamentary army towards the end of the Civil War. Following a prolonged religious crisis, in the early 1650s he experienced a religious conversion. He became a preacher, and began to publish sermons, theological treatises and poems.

Under Charles II, a determined attempt was made to suppress religious Nonconformists[4] like Bunyan, who was perceived as a threat to social order. Parliament passed a law forbidding worship and preaching outside the established Church of England. Bunyan refused to give up preaching, and as a result, he was charged with holding a service not in conformity with those of the Church of England and for this, he spent twelve years in Bedford goal.[5] When not engaged in writing, he made shoelaces to support his family, a testament to his unwavering faith and love.

Persecution was relaxed for a while but was renewed and Bunyan was imprisoned again for illegal preaching. However, this may not have been longer than six months. A bond of surety for his release, dated June 1667, and since The Pilgrim’s Progress was published in February 1678, it is probable that he began to write it, during his first imprisonment.[6]

Bunyan wrote Part 2 of The Pilgrim’s Progress, and this was published in 1684.

The Pilgrim’s Progress

The Pilgrim’s Progress is religious allegory[7] based very heavily on the Bible and written and published in two parts. The work is a vision, or dream, that recapitulates in symbolic form the story of his own conversion as Christian leaves the City of Destruction (the world) with a book (the Bible) in his hand and a great burden on his back for the Celestial City (peace, security and eventually heaven) with all its trials and tribulations. He sets off with a heavy load of sin on his back, only to have it fall off when he found SALVATION at the cross. On his journey he battles with giants and monsters such as Apollon and Giant Despair who represent his spiritual terrors. He hears the voices of Demons of the Valley of the Shadow of Death representing his own neurotic fears during his conversion. The characters he meets along the way represent different aspects of the Christian life, such as the Slough of Despond which is a swamp that Christian must cross on his journey. It represents the difficulty of the Christian life and the struggle against sin. Faithful, who represents the importance of faith. Vanity Fair, its name comes from the biblical book of Ecclesiastes, which describes the vanity of worldly pursuits. The allegory is meant to teach readers about the Christian life and to encourage them to live a life of faith and righteousness. It is a powerful work that has inspired generations of Christians, and it continues to be read and studied today.

Below, is a summary of the book taken from the Encyclopedia Britannica

Part I

John Bunyan dreaming of The Pilgrim’s Progress, 17th-century illustration.

John Bunyan dreaming of The Pilgrim’s Progress, 17th-century illustration.

Part I is presented as the author’s dream of the trials and adventures of Christian (an everyman figure) as he travels from his home, the City of Destruction, to the Celestial City. Christian seeks to rid himself of a terrible burden, the weight of his sins, that he feels after reading a book (ostensibly the Bible). Evangelist points him toward a wicket-gate, and he heads off, leaving his family behind. He falls into the Slough of Despond, dragged down by his burden, but is saved by a man named Help. Christian next meets Mr. Worldly Wiseman, who persuades him to disregard Evangelist’s advice and instead go to the village of Morality and seek out Mr. Legality or his son Civility. However, Christian’s burden becomes heavier, and he stops. Evangelist reappears and sets him back on the path to the wicket-gate. The gatekeeper, Good-will, lets him through and directs him to the house of the Interpreter, where he receives instruction on Christian grace. As Christian continues his journey, he comes upon a cross and a sepulcher, and at that point his burden falls from his shoulders. Three Shining Ones appear and give him a sealed scroll that he must present when he reaches the Celestial Gate.

Christian continues on his way, and when he reaches the Hill Difficulty, he chooses the straight and narrow path. Partway up he falls asleep in an arbor, allowing the scroll to fall from his hands. When he wakes, he proceeds to the top of the hill only to find he must return to the arbor to find his lost scroll. He later arrives at the palace Beautiful, where he meets the damsels Discretion, Prudence, Piety, and Charity. They give Christian armour, and he learns that a former neighbour, Faithful, is traveling ahead of him.

Christian next traverses the Valley of Humiliation, where he does battle with the monster Apollyon. He then passes through the terrifying Valley of the Shadow of Death. Shortly afterward he catches up with Faithful. The two enter the town of Vanity, home of the ancient Vanity Fair, which is set up to ensnare pilgrims en route to the Celestial City. Their strange clothing and lack of interest in the fair’s merchandise causes a commotion, and they are arrested. Arraigned before Lord Hate-good, Faithful is condemned to death and executed, and he is immediately taken into the Celestial City. Christian is returned to prison, but he later escapes.

Christian leaves Vanity, accompanied by Hopeful, who was inspired by Faithful. Christian and Hopeful cross the plain of Ease and resist the temptation of a silver mine. The path later becomes more difficult, and, at Christian’s encouragement, the two travelers take an easier route, through By-path Meadow. However, when they become lost and are caught in a storm, Christian realizes that he has led them astray. Trying to turn back, they stumble onto the grounds of Doubting Castle, where they are caught, imprisoned, and beaten by the Giant Despair. At last, Christian remembers that he has a key called Promise, which he and Hopeful use to unlock the doors and escape. They reach the Delectable Mountains, just outside the Celestial City, but make the mistake of following Flatterer and must be rescued by a Shining One. Before they can enter the Celestial City, they must cross a river as a test of faith, and then, after presenting their scrolls, Christian and Hopeful are admitted into the city.

Part II

The angel Secret giving Christiana a letter inviting her and her children to join her husband, Christian, in the Celestial City.

In Part II (1684) Christian’s wife, Christiana, and their sons as well as their neighbour Mercy attempt to join him in the Celestial City. The psychological intensity is relaxed in this section, and the capacity for humour and realistic observation becomes more evident. Christian’s family and Mercy—aided (physically and spiritually) by their guide Great-heart, who slays assorted giants and monsters along the way—have a somewhat easier time, because Christian has smoothed the way, and even such companions as Mrs. Much-afraid and Mr. Ready-to-halt manage to complete the journey. Whereas most of the people encountered by Christian exemplify wrong thinking that will lead to damnation, Christiana meets people who, with help, become worthy of salvation. When they reach the Celestial City, Christiana’s sons and the wives they married along the way stay behind in order to help future pilgrims.

Why is The Pilgrim’s Progress such a popular book?

The answer to its appeal lies in the fact that it is timeless and independent of ethnicity because it covers the everyday experiences of Christians and the diversions, distractions, challengers and temptations that the believer faces. The characters and places portrayed are easily recognizable and they are used in a highly predictable way with the joy of reaching the Celestial City so complete.

However, it is a hard read. It just rolls on and on and it takes commitment to read from cover to cover and yet, in Georgian and Victorian England, it was in almost every household along with the King James Bible. Fathers would read it to their children and many ordinary citizens could and would recite sections of the book when clarification of a point was required. There are many modern versions of the book as well as a range of children’s books where all the essentials are maintained in an easy-to-read format.

The book made Bunyan a highly sought after figure in his own day and in his final years he was invited to give sermons in London. Word of mouth would announce that on a certain day he was coming, and people would gather before the doors of the building opened. His friend John Doe recalled him setting out to preach at seven o’clock on a working day in the dark wintertime, and about 1200 people waiting to hear him. One Sunday about 3,000 people crammed into a big London building, and were unable to create a pathway along through which Bunyan could move from the front door to the high pulpit. He had to be lifted and carried above the heads and shoulders of the crowd. Many of the people who heard him speak felt that an inner peace had taken hold of them.[8]

Bunyan wrote many books and treatises, but The Pilgrim’s Progress is far and above all of them regarding popularity.

In 1688, while riding through the driving rain on an act of mercy of trying to resolve a dispute between a father and son, Bunyan caught a cold and was soon dead.

[1] https://books.google.com.au/books/about/The_Pilgrim_s_Progress.html?id=xc4iF-sFJn8C&redir_esc=y. https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/pilgrims/context.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pilgrim%27s_Progress.

[3] Christianity Today, https://www.christianitytoday.com/1986/07/john-bunyan-and-pilgrims-progress-did-you-know.

[4] Nonconformist, any English protestant who does not conform to the doctrines or practices of the established Church of England.

[5] W R Owens, University of Bedfordshire, writing for The International John Bunyan Society. https://johnbunyansociety.org/about-bunyan.

[6] John Bunyan, Britanica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Bunyan.

[7] A story, poem, or picture that can be interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning, typically a moral or political one.

[8] Geoffrey Blainey, A Short History of Christianity, Penguin Books, 2011, page 357.

1 Comment. Leave new

Thanks, Gary!