Introduction

Early in nineteenth century Britain there was only a handful of orphanages. These were disease and rat -infested institutions where children were forced to work long hours, barely fed and harshly treated. Early death was common. The only alternative to street begging and stealing was the dreaded workhouse. What George Muller (1805-1898) achieved during this period, by housing, feeding, clothing and educating 9,500 starving, begging orphans is astounding. He did it all by prayer with the expectation that God would answer. His policy was to never ask for any money or gifts of any sort, but to rely totally on God to provide for all his and the childrens’ needs.

Early in nineteenth century Britain there was only a handful of orphanages. These were disease and rat -infested institutions where children were forced to work long hours, barely fed and harshly treated. Early death was common. The only alternative to street begging and stealing was the dreaded workhouse. What George Muller (1805-1898) achieved during this period, by housing, feeding, clothing and educating 9,500 starving, begging orphans is astounding. He did it all by prayer with the expectation that God would answer. His policy was to never ask for any money or gifts of any sort, but to rely totally on God to provide for all his and the childrens’ needs.

So great was his work in saving orphans, that one cannot read his biography and remain the same.

What has given people an insight into his daily battles is the fact that he recorded every gift and every difficulty with meticulous detail in journals. Every single gift was recorded, whether a single farthing, £3,000, or an old teaspoon. Accounting records were meticulously kept and made available for scrutiny.

When Müller died at the age of 92 in 1898, the Daily Telegraph wrote that he had robbed the cruel streets of thousands of victims, the geals (jails) of thousands of felons, and the workhouses of thousands of helpless waifs.

The highs, lows and accomplishment of Goerge Muller’s life

George Müller was born in Germany on September 27, 1805. In his early life he was not an honest person. From the time he was ten years old he was stealing money from his father. As time passed, he also stole from his friends. Finally, he was arrested and locked up with other thieves such as him, and even with murderers. He frequented beer halls and associated with villains. One day, he came across a friend from his old university days at Halle. Beta had opened his house for pray and Bible reading of a Saturday night. Muller attended in November 1825, he felt the pull of the Holy Spirit and committed his life to Jesus.

George was spared from going into military service because of his poor health and in 1829 he went to London at the invitation of The London Society for Promoting Christianity Among Jews. However, there he became seriously ill and was sent to Teignmouth to recuperate. There, he met Henry Craik, a man who would have a huge impact on him. Henry talked with him about people who sold their possessions and gave the money to the poor. Müller was intrigued by this teaching. And decided from that time on, he would ask no one, not even fellow Christians to help him financially in any way, but to rely solely on God for all his provisions. The Mission Board said they would not support him on this basis. Craik offered him a job as pastor at Teignmouth, a small congregation of 18 members. During that year he was rebaptized as a believer.

Not long after, he fell in love with Mary Groves who also shared his convictions. Within three months they were married. Mary’s brother, Anthony Norris Groves, sold all and became a “faith missionary” They sold their possessions and gave the money to the poor. This inspired George and Mary to live a similar life.

George and Mary had four children, two of which were stillborn. The eldest, a daughter was named Lydia, and they also had a son Elijah, but he died of pneumonia when he was very young.

At the church where he preached, the people rented the pews where they sat during the services. Müller thought this was unfair to poor people who could not afford to rent a good seat. He discontinued the pew rents and put a collection box at the rear of the church. More money was collected through free-will offerings than by renting the pews.

After two years Henry Craik asked Müller, who was 26 years old at the time, to move to Bristol to work with him. In the early 1800’s orphans had no one to care for them and had to beg for or steal food to survive. People did not have pity on them, and the government put the children in workhouses where they worked long hours under the harshest of conditions. Charles Dickens’ book, Oliver Twist, brought the plight of these unfortunate children to public attention.

In 1835, with these children in mind, Müller began to pray about starting an orphan house. He recorded in his journal that apart from saving these poor wretches from the street, I wanted to demonstrate to the world that there is reality in the things of God. He wrote further, I judged myself bound, to be the servant of the church of Christ, in the particular point on which I had obtained mercy: namely, in being able to take God at his word and rely upon it. Further, he felt that God had used his encounters with Christians who lack assurance and convictions in their lives, to awaken in my heart the desire of setting before the church at large, and before the world, a proof that He had not in the least changed; and this seemed to me to be best done by establishing an orphan house.

Donations began to come in even though he didn’t solicit money from people. His vision was for the orphan home to be for children who were truly orphaned, having lost both parents. None would be turned away due to poverty or race. The children would be educated and trained for a trade.

Apart from gifts, people presented themselves, offering to teach and work in the orphanage as well. He found a place to rent and his work for orphans had commenced.

The first house he opened was for 30 girls, then, he opened a second and a third house, all in Wilson Street Bristol. The first two years went well, but the next seven years were hard. Sometimes mealtime arrived, but there was no food. They would pray and at the last minute, food would be brought for the children.

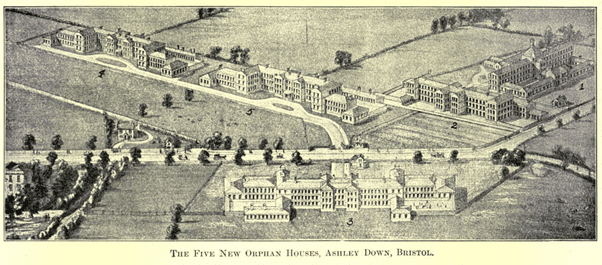

He spent hours every day studying the Bible and praying. He felt that God was calling him to care for even more orphans. After five weeks of prayer, he determined that God wanted him to build a large facility. It would be expensive, Müller estimated £10,000 which would be equivalent to over $1,000,000 in today’s money. Land was purchased at Ashley Down and construction started. This building was followed by four more, as more and more orphans were catered for. The enormous amount of money required was all through gifts after much prayer. Müller was careful not to ask for money or even let the House’s financial position be known.

On January 6, 1870, the last of Muller’s five great buildings was opened on Ashley Down, New Orphan House No 5; with this finished, the vast expansion program of orphan houses was completed. But in no sense could he sit back on his laurels. Every morning, he rose at six thirty and by a quarter to eight, after the period of prayer and Bible study, he began the task of going through his correspondence. Then, as The Times recorded some years later, at ten o’ clock he was waited on by nine assistants, to whom he gave his instructions. Note, until the 1850’s he had conducted correspondence of about three thousand letters per year without a secretary.

With the five large houses full, expenses for the children’s work now amount to thirty thousand pounds a year. Two thousand children had to be fed and clothed; their clothes washed and mended; well over two thousand pairs of shoes had to be purchased and mended. Then every year, hundreds of fresh children arrived who had to be fitted out with clothing and footwear; hundreds of boys and girls went out as apprentices and servants and had to be provided with suits of clothes at the expense of the institution. Each boy who left the home as an apprentice had a premium paid for him to his master, which was equal to about a year’s support. When any child left, his or her travelling expenses were paid.

Keeping the five enormous buildings maintained with more than 1,700 large windows and over 500 rooms was very expensive: painting, whitewashing, repairing damage and faults. Thousands of articles had to be repaired or replaced.

When the children were ill, or even died, extra expenses had to be met. The large staff at Ashley Down, including a school inspector, matrons, teachers, medical offices, nurses, Müller’s personal assistants had their salaries paid out of money which was all prayed in. But Müller recorded, we are able with as much ease, if no greater ease than very rich noblemen to accomplish this simply by looking in our poverty to the infinitely rich One for everything.[1]

The children were well clothed

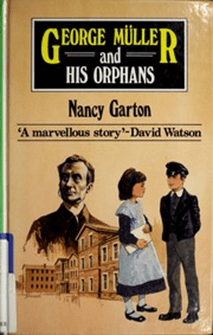

Nancy Garton describes the way the orphan children were dressed in her book, George Müller and His Orphans, published in 1963.

Nancy Garton describes the way the orphan children were dressed in her book, George Müller and His Orphans, published in 1963.

The elder boys wore a navy blue Eton jacket, with a waistcoat buttoning up to the white starched collar, both of heavy serge; brown corduroy trousers; caps with a glazed peak; and in bad weather, short cloaks. Each boy had three suits.

The small boys, up to eight or nine years old, wore for everyday, a garment which seems a strange choice from a practical point of view. It was plainly cut smock, with no collar, in white or unbleached cotton. Possibly being white, it could soon be boiled and restored to its original purity. Blue sage shorts, socks and strap shoes complete the costume. For best wear, the little boys discarded their smocks, and wore Norfolk suits with Eton collars in which they looked most attractive.

The girls outdoor dress in cold weather was a long cloak in green and blue plaid; in mild weather a shepherd’s plaid shawl took the place of the cloak; in hot weather, for best wear, the dress was a thin one of dull lilac cotton, over which was a small cape or tippet of the same material, a tiny ruff at the neck. Throughout the year, the girls wore bonnets of natural coloured straw. To each bonnet was attached a long strip of thin material with a green and white checked pattern, which formed a band across the top, crossed at back and stitched at the sides, so the two ends formed strings by which the bonnet was tied on.

Everyday dresses for girls of all ages were of navy cotton covered with small white dots, for which for walking out was added a white tippet when the weather was too warm for cloaks or shawls. In doors, the girls up to fourteen wore blue-checked gingham pinafores, cut high to the neck and buttoning behind. The girls over fourteen, who had left the schoolroom and were called ‘House Girls’ wore aprons with strings to distinguish them from their juniors. The most senior girls, those who were due to leave the Homes for situations within a few months, were known as ‘Cap Girls’, and wore caps, aprons to the waist and white collars. Every girl had five dresses.

All stockings were handknitted by the girls; black wool for the winter, and white cotton for the summer.

Their uniforms can be seen in the period photo below.

The children undertook two outings per year.

Outing for Girls. A long line of uniformed girls on an outing from George Müller’s Orphan Houses at Ashley Down, Bristol. Date: early 1900s. Mary Evans / Peter Higginbotham Collection.

The Scriptural Knowledge Institution

Back in 1834, Müller and close friend Henry Craik, created the Scriptural Knowledge Institution to support missionaries in sharing Jesus and helping disadvantaged people. During his life, Müller spent nearly £115,000 on schoolwork throughout the world, nearly £90,000 on the circulation of Bibles, Testaments, tracts and books, and over £260,000 on worldwide missionary work. All by way of faithful prayer.

Müller’s mode of prayer

The fact that so much was accomplished through prayer alone, raises the question, how did Muller pray? He did mention this in some of his sermons that four points are essential:

- Our requests must be according to God’s will

- We must not ask on account of our goodness or merit, but in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ.

- We must exercise faith in the power and willingness of God to answer our prayers.

- The final condition is that we have to continue praying, patiently waiting on God till the blessing we seek is granted.

George Müller meets his Saviour

On Thursday morning, March 10, 1998, at about seven am, his attendant knocked on his door with a cup of tea. On entering, she found him dead lying on the floor beside his bed. On his desk were the unfinished notes of a sermon he would never preach.

The following Sunday reference was made of him from every pulpit independent of denomination. Bristol’s great philanthropist, man of prayer and preacher had died. The next day, Monday March 14, was the day of his funeral. It is said that nothing like it has been seen in Bristol before and since. Firms closed or gave their employees time off to witness the event and to pay their respects; thousands of people lined the route of the procession; on Bristol cathedral and other churches flags flew half-mast and muffled peels were rung; in all the main streets they put up black shutters or drew their blinds. The city mourned.[2]

Conclusion

Anybody involved in asking for a donation for whatever cause knows that if the cause is good, people will donate. But after the initial rush of enthusiasm, money slackens off. In the case of Müller’s orphanages, giving only increased, over the growth period of sixty years. And this all happened during an impoverished Victorian England period, but the need was great. What brought about this great success, was the way humble Müller prayed to his all-powerful (omnipotent) God who delights in blessing His faithful children.

Ephesians 3:20 KJV

Now unto him that is able to do exceeding abundantly above all that we ask or think, according to the power that worketh in us,

[1] Roger Steer, George Müller Delighted in God, Christian Focus Publications, Ltd. Previously published in 1997, reprinted 2001,2004,2006 and 2008, pages 143-144.[2] Ibid, page 231.

2 Comments. Leave new

Thanks Gary, another great post of a Godly man used by God for His glory

Thank you Gary — this is the most wonderful article you have written, I believe. If only we could have faith like G.M. ! I am glad that the need is not as extreme as it was at that time and place, but it is truly amazing to see what can be accomplished thru faith and prayer! I want to say more but cannot think of the words — just many, many thanks, and I hope I can remember this article for my remaining years.