The Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary of 2011 makes the following comment on Mark’s gospel: On two points the tradition of the early church is unanimous: the second gospel was written by John Mark and presents the teaching of Peter.

The Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary of 2011 makes the following comment on Mark’s gospel: On two points the tradition of the early church is unanimous: the second gospel was written by John Mark and presents the teaching of Peter.

The image is taken from Fr. Michael McGourty, Pastor— St. Peter’s Church— Toronto.

Introduction

Each of the gospel writers are unique.

Matthew was a Jew, and he directed his writing to Jewish readers, showing that the Old Testament prophecies regarding the promised Messiah were fulfilled in the Person of Jesus of Nazareth. He wrote it himself based on his own observations as he travelled with Jesus.

Luke states the reason he wrote his gospel and Acts as well, in the first four verses:

Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. With this in mind, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I too decided to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught.

It is possible that he went to the extent of interviewing Jesus’ mother Mary, because he gives an account of the twelve-year-old Jesus staying at the temple and discussing the scriptures with the teachers (Luke 2:41-52).

John was a Jew and one of the disciples. He gives his reason for writing in verses 30-31 of chapter 20:

“Therefore many other signs Jesus also performed in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; but these have been written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing you may have life in His name.”

Mark’s gospel

Mark commences his gospel with John the Baptist heralding the coming Messiah. He neglects mentioning the virginal conception of Jesus and the events that surrounded His birth. As well, he finishes with the women seeing the empty tomb and being told by an angel (a young man dressed in a white robe) that Jesus had risen and for them to tell his disciples and Peter.

What we know about Mark from scripture

John was his Jewish name, Mark (Marcus) his Roman name. In the book of Acts, he is simply referred to as John (13:5, 13), once as Mark (15:39), and three times as “John also called Mark” (12:12, 25, 15:37). In the Letters he is simply called Mark.

His mother’s name was Mary (Acts 12:12). She was a Christian woman and had a large house with servants where believers would gather. In fact, in the Acts account given above, members of the early church were praying in Mary’s house, for Peter to be released from prison. And it was to Mary’s house that Peter went when he was miraculously released. Also, she was related to Barnabas, and Mark is described as Barnabas’ cousin (Colossians 4:10).

Mark accompanied Paul and Barnabas on Paul’s first missionary journey (Acts 12:25; 13:5) but left them at Perga and returned to Jerusalem (Acts 13:13). Whatever the reason for his desertion, it was enough for Paul to refuse to take him on his next journey, so he split with Barnabas and went with Silas. Paul’s opinion of Mark improved greatly as Mark was with him during his first imprisonment in Rome (Colossians 4:10; Philemon 24). Later during Paul’s final imprisonment before his execution, he requested Timothy to bring Mark with him to Rome (2 Timothy 4:11).

What we know about Mark from the early church

Mark is not mentioned in his gospel as having any eyewitness account, so how did he get his information regarding the ministry of Jesus?

Mark is not mentioned in his gospel as having any eyewitness account, so how did he get his information regarding the ministry of Jesus?

Early Christian apologist, Justin Martyr, wrote Dialogue with Trypho (approximately AD 150) and included this interesting passage:

It is said that he [Jesus] changed the name of one of the apostles to Peter; and it is written in his memoirs that he changed the names of others, two brothers, the sons of Zebedee, to Boanerges, which means ‘sons of thunder’….

Justin, therefore, identified a particular Gospel as the ‘memoir’ of Peter and said this memoir described the sons of Zebedee as the ‘sons of thunder’. Only Mark’s Gospel describes John and James in this way, so it is reasonable to assume that the Gospel of Mark is the memoir of Peter.[1]

Eusebius (AD 260-339) was the bishop in Caesarea and was the first Christian historian. He fills in the time from when the New Testament ended to the time of Constantine under whose direction Christianity became the state religion.

In his book, Eusebius The Church History,[2] Dr Paul L Maier presents a word for word translation of Eusebius’s Church History, he makes the following comment: It is most fortunate that Eusebius quotes his sources extensively, since many of them have been lost and would not have survived, even in fragments had Eusebius not incorporated them into his history.

In his book, Eusebius The Church History,[2] Dr Paul L Maier presents a word for word translation of Eusebius’s Church History, he makes the following comment: It is most fortunate that Eusebius quotes his sources extensively, since many of them have been lost and would not have survived, even in fragments had Eusebius not incorporated them into his history.

In reference to Mark’s gospel, Eusebius writes: Peter’s hearers, not satisfied with a single hearing or with the unwritten teaching of the divine message, pleaded with Mark, whose gospel we have, to leave them a written summary of the teaching given them verbally, since he was a follower of Peter. Nor did they cease until they persuaded him and so called the Gospel according to Mark. It is said that the apostle was delighted at their enthusiasm and approved the reading of the book in the churches. Clement quotes the story in outlines, Book 6, and Bishop Papias of Hierapolis confirms it.[3]

Papias was a Greek Apostolic Father, Bishop of Hierapolis, and author who lived from about AD 60 – about 130. His writings have been lost. Eusebius records him as stating in relation to Mark, Mark became Peter’s interpreter and wrote down accurately, but not in order, all that he remembered of the things said and done by the Lord. For he had not heard the Lord or been one of his followers, but later, as I said, a follower of Peter. Peter used to teach as the occasion demanded, without giving systematic arrangement to the Lord’s sayings, so that Mark did not err in writing down some things just as he recalled them. For he had one overriding purpose: to omit nothing that he had heard and to make no false statements on his account.[4]

Irenaeus of Lyons (AD 130-202) was a second-century Christian theologian and writer who wrote his Against Heresies, a refutation of Gnosticism and a defense of the four-fold gospel. He had seen and heard the preaching of Polycarp, who in turn was said to have heard John the Evangelist, and thus was the last-known living connection with the Apostles. However, none of his works aside from Against Heresies and The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching survive today.

In Book 3, in reference to Mark’s gospel, Eusebius has written, Matthew composed a written gospel for the Hebrews in their own language, while Peter and Paul were preaching the gospel in Rome and founding the church there. After their deaths, Mark too, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, handed on to us in writing the things proclaimed by Peter.

As well as the above, Eusebius quotes Clement of Alexandria[5] (c.150-c.215) [image drawn in 1585] and claims that he (Eusebius) has all his major writings. Regarding Mark’s gospel which Clement included in his Outlines Eusebius writes: In the same books, Clement has included a tradition of the earliest elders regarding the order of the gospels, namely, that those with genealogies were written first and that Mark originated as follows. When, by the Spirit, Peter had publicly proclaimed the gospel in Rome, his many hearers urged Mark, as one who had followed him for years and remembered what was said, to put it all in writing. This he did and gave copies to all who asked. When Peter learned of it, he neither objected nor promoted it.

As well as the above, Eusebius quotes Clement of Alexandria[5] (c.150-c.215) [image drawn in 1585] and claims that he (Eusebius) has all his major writings. Regarding Mark’s gospel which Clement included in his Outlines Eusebius writes: In the same books, Clement has included a tradition of the earliest elders regarding the order of the gospels, namely, that those with genealogies were written first and that Mark originated as follows. When, by the Spirit, Peter had publicly proclaimed the gospel in Rome, his many hearers urged Mark, as one who had followed him for years and remembered what was said, to put it all in writing. This he did and gave copies to all who asked. When Peter learned of it, he neither objected nor promoted it.

Another early writer who Eusebius quotes regarding the genesis of Mark’s gospel is Origen.[6] In his Commentary on Matthew, he writes, I learned by tradition that the four gospels alone are unquestionable in the church of God. First to be written was by Matthew, who was once a tax collector but later an apostle of Jesus Christ, who published in Hebrew for Jewish believers. The second was by Mark, who wrote it following Peter’s directives, whom Peter also acknowledged as his son in his epistle: “The church in Babylon greets you …. And so does my son Mark” (1 Peter5:13). The third is by Luke, who wrote the gospel praised by Paul for Gentile believers. After them all came John’s.

So, Eusebius in his The Church History which he wrote in the early fourth century, quotes other earlier church historians going back to the late first, or early second century, all in agreement that Mark wrote his gospel when he was in Rome listening to Peter preach. He wrote it at the request of the people while Peter was still alive (Clement).

Tertullian affirmed Peter’s influence on the Gospel of Mark

Early Christian theologian and apologist, Tertullian (AD 160-225), wrote a book that refuted the theology and authority of Marcion. The book was appropriately called, Against Marcion and in Book 4 Chapter 5, he described the Gospel of Mark:

While that [gospel] which Mark published may be affirmed to be Peter’s whose interpreter Mark was.

Critics of Mark’s gospel

The brevity of Mark’s gospel of only 16 chapters (Matthew 28, Luke 24, and John 21), his rush to tell the events of Jesus’ life, often using the word, “immediately” and his seemingly incomplete start and finish has led many scholars to question the legitimacy of the whole gospel and even asking, did Mark really write it?[7]

As shown, there is significant agreement among early Christian writers (church fathers), that it was Mark who wrote it. And further, that Mark wrote from Peter’s preaching and no doubt personal conversations as Peter refers to Mark as My son Mark (1 Peter 5:13). Both were in Rome together.

This explanation of how Mark’s gospel was written, provides an understanding of the lack of an account of Jesus’ virginal conception and the events that surrounded His birth. Maybe Peter was not aware of the details of this. Peter’s impetuous nature could explain why Mark moves so quickly through the events of Jesus’ ministry.

This explanation of how Mark’s gospel was written, provides an understanding of the lack of an account of Jesus’ virginal conception and the events that surrounded His birth. Maybe Peter was not aware of the details of this. Peter’s impetuous nature could explain why Mark moves so quickly through the events of Jesus’ ministry.

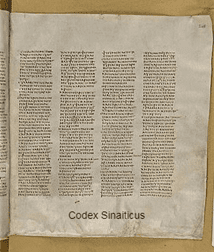

The ending of Mark’s gospel has caused much discussion. Some Bibles, particularly the King James Version include verses 9-19 of chapter 16. These verses appear to have been added later as they are not present in the earliest and most reliable copies of Mark such as the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus which do not contain them. Bruce Metzger writes: Clement of Alexandria and Origen show no knowledge of the existence of these verses: furthermore Eusebius and Jerome attest that the passage was absent from almost all Greek copies of Mark known to them.[8] Further, these extra verses display certain peculiarities of vocabulary, style and theological content and are unlike the rest of Mark.[9]

Maybe Mark did write more, and the final pages have been lost.

Conclusion

The evidence for the fact that Mark wrote his gospel after hearing Peter talk about his eyewitness experiences with Jesus and being part of Jesus’ earthly ministry and that this took place in Rome during the latter part of Peter’s life, is very strong. Supporting statements from the following early church fathers are from Papias (Greek approx. AD 60-130), Irenaeus of Lyons (AD 130-202), Justin Martyr (c.100-c.165) Clement of Alexandria (c.150-c.215), Tertullian (AD 160-225) and Origen of Alexandria (c.185 – c.253).

As to the order of the four gospels, Irenaeus of Lyons gives a strong indication that Matthew’s gospel appeared first and then Mark’s. Origin states clearly that Matthew’s gospel was written first, then it was followed by Mark’s.

When we read Mark, we can be confident of the early church’s assessment of it, its fidelity, and its placement as the second gospel.

[1] https://coldcasechristianity.com/writings/is-marks-gospel-an-early-memoir-of-the-apostle-peter.[2] Dr Paul L Maier, Eusebius The Church History, Kregel Publications, 1999.

[3] Ibid page 73.

[4] Ibid page 129-130.

[5] Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (150 – c. 215 AD), was a Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria.

[6] Origen of Alexandria (c. 185 – c. 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Alexandria. Origen was able to produce a massive quantity of writings because of the patronage of his close friend Ambrose of Alexandria, who provided him with a team of secretaries to copy his works, making him one of the most prolific writers in all of antiquity.

[7] Many liberal theologians question the validity of Mark’s gospel. One of the most vociferous is Dr James Tabor; https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/new-testament/the-strange-ending-of-the-gospel-of-mark-and-why-it-makes-all-the-difference.

[8] Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd edition, Hendrickson Publishers, 2005, page 123.

[9] The NIV Study Bible, New International Version, Zondervan Bible Publishers, 1985, page 1530.