Introduction

There are two Philips mentioned in the New Testament. One is a disciple (apostle) and the other an evangelist. The following are the biblical references to both.

Philip the Apostle

Jesus called Philip to be a disciple (John 1:43–51) and consequently, Philip is present in every list of the Apostles which are given; (Matthew 10:2-4, Mark 3:14-19, Luke 6:13-16, and Acts 1:13-16). It was Philip who brought the boy’s lunch to Jesus, who used it to feed the multitude (John 6:5-7). Philip introduces some Greeks to Jesus (John12:20-22). Philip asks Jesus about the Father (John 14:8-9).

Philip the Evangelist

He was one of the seven who were selected to wait at tables (Acts 6:5). Philip preached in Samaria (Acts 8:4-6). Philip explains Isaiah to the Ethiopian eunuch and baptised him (Acts 8:26-39). He preached in Azotus (Acts 8:40). Paul stayed at Philip’s house (Acts 21:8-9).

Where did Philip the Apostle die?

Polycrates letter

Polycrates, Bishop of Ephesus, wrote to Pope Victor I in about AD 196[1] regarding his opposition to changing the Paschal Feast known as Passover which was on Nissan 14 to Easter. In the letter he refers to Philip the Apostle and states:

Polycrates, Bishop of Ephesus, wrote to Pope Victor I in about AD 196[1] regarding his opposition to changing the Paschal Feast known as Passover which was on Nissan 14 to Easter. In the letter he refers to Philip the Apostle and states:

Philip, one of the twelve apostles who fell asleep at Hierapolis. I speak of Philip, one of the twelve apostles, who is laid to rest at Hierapolis; and his two daughters, who arrived at old age unmarried; his other daughter also, who passed her life under the influence of the Holy Spirit, and reposes at Ephesus.

Image credit: Biblical Archaeology Review 37:4, July/August 2011.

Eusebius

Eusebius refers to Polycrates letter to Pope Victor I and to the fact that the apostle Philip died at Hierapolis along with his two daughters.[2]

Further, he quotes Papias (AD 70-163) contemporary of Philip’s daughters Irais and Chariline. Papias was the Bishop of Hierapolis and also during the daughters’ elder years, presumably after their father had died. He is known to have written one of the earliest histories of the Christian church’s beginnings. Among the authorities Papias relied upon were Philip’s two daughters, who he knew personally. According to Eusebius, Papias described how people would travel long distances to hear the two sisters tell their stories of the early church.[3]

Please note, there may have been some confusion amongst these early writers regarding the two Philips. Philip the evangelist had four unmarried daughters (Acts 21:9). Philip the apostle may have had unmarried daughters as well as stated by Polycrates and referred to by Eusebius.

Acts of Philip

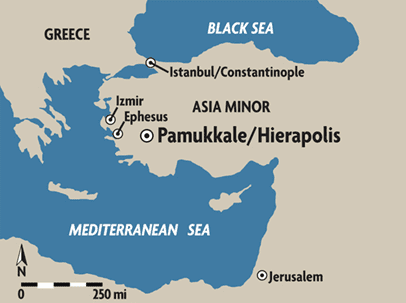

The apocryphal, non-canonical Acts of Philip state that Philip and Bartholomew, one of the twelve, and Philip’s sister Mariamne preached in Syria, Asia Minor and then in Phrygia. It was in Hierapolis where Philip was crucified upside down at the age of about 85.[4] Please note, the books that comprise the Apocrypha were not included in the cannon of scripture because of many inconsistencies with scripture, but they can, and in many cases do, contain truth.

Professor Francesco D’ Andria notes that the description of Hierapolis in the Acts of Philip is consistent with the site’s unusual geological features being on a highly active fault line giving rise to hot springs.[5]

The discovery of Philip’s tomb

After an agreement between the Turkish and Italian authorities in 1958, Professor Paolo Verzone started excavating the remains of Philip’s martyrium[6] at Hierapolis in a search for Philip’s tomb. The expedition was part of an Italian archaeological project. In this work, Verzone and his team uncovered an extraordinary octagonal church, a genuine masterpiece of Byzantine architecture of the fifth century, with wonderful arches of travertine stone, shown. It consisted of a large octagonal structure enclosed by a rectangle portico consisting of 28 small square rooms. Within the octagon are eight chapels, which end in four triangular courtyards in the corners of the rectangle.

After an agreement between the Turkish and Italian authorities in 1958, Professor Paolo Verzone started excavating the remains of Philip’s martyrium[6] at Hierapolis in a search for Philip’s tomb. The expedition was part of an Italian archaeological project. In this work, Verzone and his team uncovered an extraordinary octagonal church, a genuine masterpiece of Byzantine architecture of the fifth century, with wonderful arches of travertine stone, shown. It consisted of a large octagonal structure enclosed by a rectangle portico consisting of 28 small square rooms. Within the octagon are eight chapels, which end in four triangular courtyards in the corners of the rectangle.

Professor Francesco D’ Andria took over Verzone’s work. In an interview by Renzo Allegri of Zenit Daily Dispatch on May 2, 2012,[7] D’ Andria states: I myself thought the tomb was in the area of the church, but in 2000, when I became director of the Italian archaeological mission of Hierapolis, by concession of the Ministry of Culture of Turkey, I changed my opinion.

ZENIT: Why?

D’Andria: All the excavations carried out over so many years had no result. I also carried out research through geo-physical explorations, that is, special explorations of the subsoil, and not obtaining anything, I was convinced we had to look elsewhere, still in the same area but in another direction.

ZENIT: And towards what did you direct your research?

D’Andria: My collaborators and I studied a series of satellite photos of the area carefully, and the observations of a group of brave topographers of the CNR-IBAM, directed by Giuseppe Scardozzi, and we understood that the Martyrion, the octagonal church was the center of a large and well-developed devotional complex. We identified a great processional street that took the pilgrims of the city to the octagonal church, the Martyrion at the top of the hill, the remains of a bridge that enabled pilgrims to go across a valley through which a torrent flowed; we say that at the foot of the hill there were stairs in travertine stone, with wide ascending steps that led to the summit.

At the bottom of the stairs, we identified another octagonal building that could not be seen from the surface but only on satellite photos. We excavated around that building and realized it was a thermal complex.

This was an enlightening discovery that made us understand that the whole hill was part of a course of pilgrimage with several stages. Continuing our excavations, we found another flight of steps that led directly to the Martyrion, and on the Square, next to the Martyrion, there was a fountain where pilgrims did their ablutions with water, and near there a small plain, in front of the Martyrion, where there were vestiges of buildings. Professor Verzone had not dared to carry out an excavation in that area because it was an immense heap of stones. In 2010, we began to do some cleaning and elements of extreme importance came to light.

ZENIT: Of what sort?

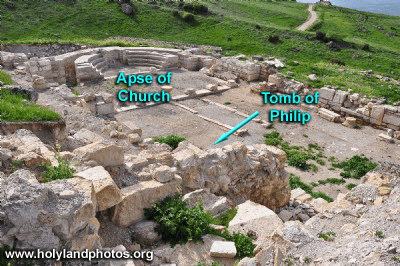

D’Andria: A marble architrave of a ciborium with a monogram on which the name Theodosius could be read. I thought it was the name of the emperor and so that architrave made it possible to date the martyrial church between the fourth and fifth centuries. Then, little by little we found vestiges of an apse. Excavating and cleaning the floor, a great church came to light. Whereas the floor of the Martyrion was octagonal, this floor was that of a basilica, with three naves. A stupendous  church with marble capitals refined decorations, crosses, friezes, plant branches, stylized palms in the niches and a central pavement with marble tesserae with colored geometrical motifs: all referable to the fifth century, namely, the age of the other church, the Martyrion. However, at the center of this wonderful construction what enthused and moved us was something disconcerting that left us breathless.

church with marble capitals refined decorations, crosses, friezes, plant branches, stylized palms in the niches and a central pavement with marble tesserae with colored geometrical motifs: all referable to the fifth century, namely, the age of the other church, the Martyrion. However, at the center of this wonderful construction what enthused and moved us was something disconcerting that left us breathless.

ZENIT: And it was?

D’Andria: A typical Roman tomb that went back to the first century after Christ. In a certain sense, its presence could be justified by the fact that in that area, before Christians built the proto-Byzantine shrine, there was a Roman necropolis. However, examining its position carefully, we realized that that Roman tomb was at the center of the church. Hence, in the fifth century the church had been built precisely around that pagan Roman tomb, to protect it, because, evidently, that tomb was extremely important. And immediately we thought that perhaps that could be the tomb where the body of St. Philip was placed after his death.

ZENIT: And did you find confirmations of this supposition?

D’Andria: Indeed. In the summer of 2011, we carried out extensive excavation in the area of this church with the coordination of Piera Caggia, research archaeologist of the IBAM-CNR, and extraordinary elements emerged that confirmed our suppositions fully. The tomb was included in a structure in which there is a platform that is reached by a marble staircase. Pilgrims, entering the narthex, went up to the higher part of the tomb, where there was a place for prayer and they went down on the opposite side. And we saw that the marble surface of the steps was completely consumed by the steps of thousands upon thousands of people. Hence, the tomb received an extraordinary tribute of veneration.

On the façade of the tomb, near the entrance, there are nail holes which undoubtedly served to support an applied metallic locking device. Moreover, there are grooves in the pavement that make one think of an additional wooden door: all precautions that indicate that in that tomb there was an inestimable treasure, namely, the apostle’s body.

On the façade of the tomb, near the entrance, there are nail holes which undoubtedly served to support an applied metallic locking device. Moreover, there are grooves in the pavement that make one think of an additional wooden door: all precautions that indicate that in that tomb there was an inestimable treasure, namely, the apostle’s body.

The image is of Professor D’ Andria standing outside the apostle Philip’s tomb. Image credit: Orthodox Christianity Now and Then, https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2011/07/tomb-of-apostle-philip-discovered-in.html.

And on the façade, on the walls there are numerous graffiti with crosses, which in some ways have consecrated the pagan tomb.

Excavating next to the tomb we found water baths for individual immersions, which undoubtedly served for healings. After venerating the tomb, sick pilgrims were submerged in the baths exactly as happens in Lourdes.

However, the main — I would say mathematical — confirmation which attests, without a shadow of a doubt, that that construction is really St. Philip’s tomb comes from a small object that is in the Museum of Richmond in the United States. An object in which there are images that up to now could not be fully deciphered, whereas now they have an obvious significance.

ZENIT: What object is it?

D’Andria: it is a bronze seal about 10 centimeters (four inches) in diameter, which served to authenticate St. Philip’s bread to be distributed to pilgrims. Icons have been found that represent St. Philip with a large loaf in his hand. And to be distinguished from ordinary bread, this bread was marked with the seal so that pilgrims would know that it was a special bread, to be kept with devotion.

There are images on the seal. There is the figure of a saint with a pilgrims’ cloak and an inscription that says “Saint Philip.” On the border is a phrase in Greek, an ancient phrase of praise to God: Agios o Theos, agios ischyros, agios athanatos, eleison imas (Holy God, strong Holy One, immortal Holy One, have mercy on us). All the specialists of Byzantine history who know that seal have always said that it came from Hierapolis. However, what is most extraordinary is the fact that the figure of the saint is presented between two buildings: the one on the left is covered by a cupola, and it is understood that it represents the octagonal Martyrion; the one on the right of the saint, has a roof like the one of the church of three naves which we have now discovered. The two buildings are at the top of a stairway. It seems that it was an image of the complex then existing around St. Philip’s tomb. A photograph made in the sixth century. Moreover, in the image of the seal there is an emblematic element: a lamp hanging at the entrance, typical signs that served to indicate a saint’s sepulcher. Hence, already indicated in that seal is that the tomb was in the basilica church and not in the Martyrion.

There are images on the seal. There is the figure of a saint with a pilgrims’ cloak and an inscription that says “Saint Philip.” On the border is a phrase in Greek, an ancient phrase of praise to God: Agios o Theos, agios ischyros, agios athanatos, eleison imas (Holy God, strong Holy One, immortal Holy One, have mercy on us). All the specialists of Byzantine history who know that seal have always said that it came from Hierapolis. However, what is most extraordinary is the fact that the figure of the saint is presented between two buildings: the one on the left is covered by a cupola, and it is understood that it represents the octagonal Martyrion; the one on the right of the saint, has a roof like the one of the church of three naves which we have now discovered. The two buildings are at the top of a stairway. It seems that it was an image of the complex then existing around St. Philip’s tomb. A photograph made in the sixth century. Moreover, in the image of the seal there is an emblematic element: a lamp hanging at the entrance, typical signs that served to indicate a saint’s sepulcher. Hence, already indicated in that seal is that the tomb was in the basilica church and not in the Martyrion.

ZENIT: You have made all these discoveries in recent times.

D’Andria: I would say very recent times. We did so between 2010 and 2011. Above all 2011 was the year of the greatest emotions for us: we discovered the second church and Philip’s tomb. We concluded a work begun 55 years ago. The news has gone around the world. And it has attracted scholars and the curious to Hierapolis. Among others, at the end of last August, hundreds of Chinese arrived, as well as numerous Koreans and journalists of several nationalities.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that the tomb of the apostle Philip has been discovered, but his body was not present. Professor D’ Andria has this to say as to what happened to Philip’s body; On an unspecified date, Philip’s body was taken to Constantinople to remove it from the danger of profanation by barbarians. And in the sixth century, under Pope Pelagius I, it was taken to Rome and buried, next to the Apostle James, in a church built specifically for them. The Byzantine-style church, which was called “of Sts. James and Philip,” was transformed in 1500 into a magnificent Renaissance church, which is the present one called “Of the Holy Apostles.”

[1] Polycrates’ Epistle to Victor and the Roman Church, https://www.academia.edu/49314971/Polycrates_Epistle_to_Victor_and_the_Roman_Church[2] Paul Maier, Eusebius The Church History, Kregel Publications, 1999, page 198.

[3] Mark Carlson-Ghost, citing Eusebius, History, 3.39.9.

[4] The Apocryphal New Testament, M.R. James-Translation and Notes, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924, Verses 131-146. http://www.gnosis.org/library/actphil.htm.

[5] Conversations, Crucifixion and Celebration, https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/37/4/2.

[6] A martyrium (Latin) or martyrion (Greek), plural martyria, sometimes anglicized martyry, is a church or shrine built over the tomb of a Christian martyr. It is associated with a specific architectural form, centred on a central element and thus built on a central plan, that is, of a circular or sometimes octagonal or cruciform shape.

[7] How I Discovered the Tomb of the Apostle Philip, https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/how-i-discovered-the-tomb-of-the-apostle-philip-1949.