The Black Death

The Black Death originated in China and Genoese ships carried the epidemic westward to Mediterranean ports, from where it spread inland via trade routes. In the years 1346 to 1353 Europe was ravaged by the first wave of the Black Death also known as the Bubonic Plague as swollen lymph nodes (buboes) often occur in the neck, armpit and groin (inguinal) regions of plague victims. The bacterium responsible was Yersinai pestis and the infection was spread by fleas living on rats which were endemic throughout Europe. Once bitten the bacterium would enter the victim’s blood, the lymph glands in the neck, arm pits and groin would swell, become septic with pus oozing out and death would occur within five to seven days. As the infection progresses, blood flow to the extremities is greatly reduced and fingers and toes turn black.

An estimated 75 to 200 million people died. In some places half the population died.

For the next three centuries, outbreaks of the plague occurred frequently throughout the continent and the British Isles. The Great Plague of London of 1664–66 caused between 75,000 and 100,000 deaths in a  population estimated at 460,000. The plague raged in Cologne and on the Rhine from 1666 to 1670 and in the Netherlands from 1667 to 1669, but after that it seems to have subsided in western Europe. Between 1675 and 1684 a new outbreak appeared in North Africa, Turkey, Poland, Hungary, Austria, and Germany, progressing northward. Malta lost 11,000 persons in 1675, Vienna at least 76,000 in 1679, and Prague 83,000 in 1681. Many northern German cities also suffered during this time.[1]

population estimated at 460,000. The plague raged in Cologne and on the Rhine from 1666 to 1670 and in the Netherlands from 1667 to 1669, but after that it seems to have subsided in western Europe. Between 1675 and 1684 a new outbreak appeared in North Africa, Turkey, Poland, Hungary, Austria, and Germany, progressing northward. Malta lost 11,000 persons in 1675, Vienna at least 76,000 in 1679, and Prague 83,000 in 1681. Many northern German cities also suffered during this time.[1]

Bubonic plague still occurs throughout the world with cases in Africa, Asia, South America and the western areas of North America appearing in the 20th and 21st centuries. Between 1900 and 1925, there were 12 major plague outbreaks in 27 localities of Australia introduced by infected rats from overseas ships. According to Government health archives, there were 1371 reported cases of plague and 535 deaths.[2]

Yersinia pestis is now controlled by vaccination and antibiotics are effective in attacking and destroying the bacterium.

Image credits: Wikimedia commons

Oberammergau

It is the year 1632, the beautiful, remote town of Oberammergau (pronounced oh-ber-AH-mer-gow) nestled in the Bavarian Alps of Southern Germany, was quietly  and securely isolated from the turmoil, torment and fear of the Bubonic plague that ravaged the rest of Europe. A humble wood carver, Kasper Schisler, returned to his home from his labours in a nearby village. But unbeknown to him and the other inhabitants of the town, he silently carried with him the seeds of a calamity that will wreak havoc, terror and destruction on Oberammergau and its people. Within a year of that day, 84 people out of a population of about 600, had died, claimed by the dreaded plague; the Black Death. This calamity will give rise to an extraordinary covenant with God that still lives today, almost 400 years later.

and securely isolated from the turmoil, torment and fear of the Bubonic plague that ravaged the rest of Europe. A humble wood carver, Kasper Schisler, returned to his home from his labours in a nearby village. But unbeknown to him and the other inhabitants of the town, he silently carried with him the seeds of a calamity that will wreak havoc, terror and destruction on Oberammergau and its people. Within a year of that day, 84 people out of a population of about 600, had died, claimed by the dreaded plague; the Black Death. This calamity will give rise to an extraordinary covenant with God that still lives today, almost 400 years later.

Credit for the picture of Oberammergau: Laetitia Vancon for the New York Times

The promise

The villagers of Oberammergau gathered in front of a large crucifix, which still hangs in their parish church. They vowed that if God would halt the plague, they would enact the last week of Jesus’ life, His suffering, death and resurrection, as a thank offering. The people had suffered greatly, but they knew Someone who had suffered even more; Jesus Christ. They promised God that every ten years they would stage a passion (Latin for suffering) play to show how Jesus had suffered. They wanted to thank God for saving their village.

God stopped the plague immediately and the people kept their promise.

Pastor Daisenberger writes in his village chronicles: The first decades of the 17th century went by in peaceful calm for the people of Oberammergau. But then followed the Thirty Years’ War with all its hardships from 1618 until 1648, which under the name of the Swedes’ War lives on the memory of the people. As early as 1631, infectious diseases spread in Swabia as well as in Bavaria. This village was spared by dutiful vigilance until the church festival in 1632, when a man named Kaspar Schisler brought the plague into the village. Faced with the great distress that the terrible illness inflicted upon the population, the leaders of the community came together and pledged to hold a passion tragedy once every ten years. From this day forward, not a single person perished, even though a great number of them still showed signs of the plague.[3]

Kathern Bennhold wrote in the New York Times, April 5, 2020

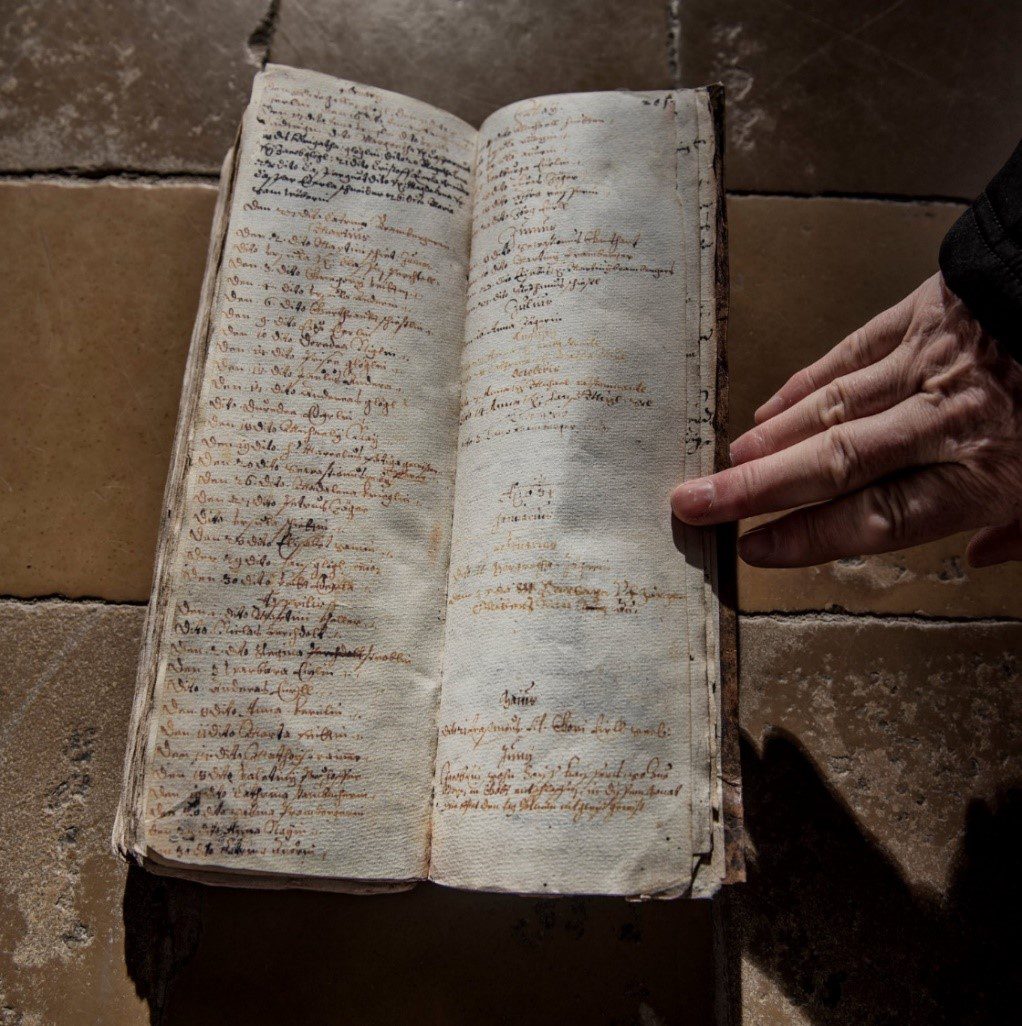

It was 1633. The bubonic plague was still raging in Bavaria. But legend has it that after the pledge, no one else in the village died from it. Standing in his church underneath the cross where villagers had once made their promise, Father Gröner held out a battered leather-bound book. “Look,” he said, his fingers scanning a faded page with tightly packed handwriting that abruptly stops three quarters down. “They recorded dozens and dozens of deaths and then — none.”

It was 1633. The bubonic plague was still raging in Bavaria. But legend has it that after the pledge, no one else in the village died from it. Standing in his church underneath the cross where villagers had once made their promise, Father Gröner held out a battered leather-bound book. “Look,” he said, his fingers scanning a faded page with tightly packed handwriting that abruptly stops three quarters down. “They recorded dozens and dozens of deaths and then — none.”

In 1634, since there were no more deaths and life gradually returned to normal, the whole village, put on their first passion play; it was performed in a meadow in front of the church. All of the actors lived in the village, and even though they weren’t professional actors, they worked hard and their play was very good. From 1680 they decided to hold it at the start of each decade. Since many people could not read, the play became the “poor man’s Bible.”

Over the decades and centuries, Oberammergau has put on their now, internationally known “Passion Play.” Over 2000 of the village’s 5000 inhabitants take part, as actors, choristers, musicians, stage hands and more. The rules are simple: you have to have been born in Oberammergau, or have lived there for 20 years. They spend two years preparing for their performances, each of the 21 lead roles is allocated to two actors, one being a backup. The men spend a year prior to the performance, growing their hair and beards.

The theatre hosts 5000 spectators who come from all over the world. The tourism created by the Passion play has a major economic impact on Oberammergau. A local expression “Die Passion zahlt” translates as “the passion play will pay for it”. It has, in fact, paid for a community swimming pool, community centre and many other improvements to the village.

The theatre hosts 5000 spectators who come from all over the world. The tourism created by the Passion play has a major economic impact on Oberammergau. A local expression “Die Passion zahlt” translates as “the passion play will pay for it”. It has, in fact, paid for a community swimming pool, community centre and many other improvements to the village.

There have been few postponements of the play. In 1770, Elector Maximilian III, then Duke of Bavaria, banned all passion plays, as part of a drive against extravagance. A new ruler reviewed the play, and performances were allowed once again in 1780. The 1920 performance was postponed due to post-war economic conditions, and the 1940 performance was cancelled due to the onset of the Second World War in 1939. Now, 90 years later, the 42nd edition  of the Passion Play scheduled from May to October 2020, has been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The 42nd Oberammergau Passion Play will now take place from 14 May to 2 October 2022.

of the Passion Play scheduled from May to October 2020, has been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The 42nd Oberammergau Passion Play will now take place from 14 May to 2 October 2022.

The stage of the Passion Play Theatre was erected in 1930 and the auditorium was extended to 5,200 seats.

Conclusion

Examples of people coming together to cry out to God for the deliverance of some potential catastrophe are very rare outside of the Bible, but they do exist. There are the people of Oberammergau who cried out to the Lord almost 400 years ago. Another is the people of Britain who held a National Day of Prayer; Sunday, May 26, 1940 and 338,226 men were snatched from the jaws of death or imprisonment. See my blog about the Miracle of Dunkirk here: https://www.adefenceofthebible.com/2016/02/02/the-miracle-of-dunkirk.

These two great gracious acts of God are consistent with His word:

…if my people, who are called by my name, will humble themselves and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven, and I will forgive their sin and will heal their land. 2 Chronicles 7:14.

[1] Encyclopedia Britannia online. [2] The University of Sydney School of Medicine. https://www.sydney.edu.au/medicine/museum/mwmuseum/index.php/Bubonic_Plague_comes_to_Sydney_in_1900. [3] The Passion Play’s website: https://www.passionsspiele-oberammergau.de/en/play/history/2.2020-03-02.