The discovery

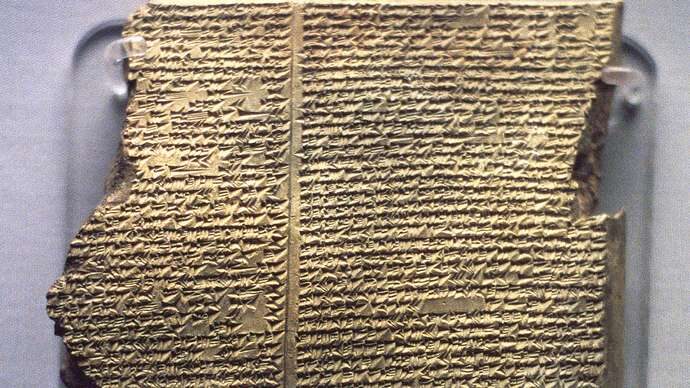

George Smith, a British explorer and language expert was sifting through clay tablets in the British Museum, that were part of a much larger collection of 25,000 recovered from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in ancient Nineveh. They were unearthed by British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in 1853. As Smith read what has become known as the Epic of Gilgamesh recorded on a twelve-tablet set, he came across a story on the eleventh tablet, of a great flood that was remarkedly similar to the Genesis account, but it was incomplete. His report of this discovery prompted The Daily Telegraph of London to sponsor an expedition to find the missing fragment needed to complete the deluge account. In May 1873, on the fifth day of digging at Nineveh, Smith found the fragment.[1]

recovered from the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in ancient Nineveh. They were unearthed by British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard in 1853. As Smith read what has become known as the Epic of Gilgamesh recorded on a twelve-tablet set, he came across a story on the eleventh tablet, of a great flood that was remarkedly similar to the Genesis account, but it was incomplete. His report of this discovery prompted The Daily Telegraph of London to sponsor an expedition to find the missing fragment needed to complete the deluge account. In May 1873, on the fifth day of digging at Nineveh, Smith found the fragment.[1]

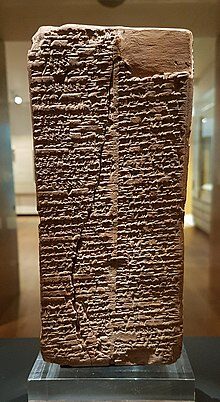

Pictured: The Flood Tablet, 11th cuneiform tablet in a series relating the Gilgamesh epic, in the British Museum, London. © Photos.com/Jupiterimages.

The result

On December 3, 1872, Smith (pictured) lectured to an overflow audience including the Prime Minister William Gladstone, of the Biblical Archaeological Society. Smith told his audience that he had read on one of the tablets, a flood story very similar to that recorded in the book of Genesis.[2] Smith published his work in 1872 as well.[3]

On December 3, 1872, Smith (pictured) lectured to an overflow audience including the Prime Minister William Gladstone, of the Biblical Archaeological Society. Smith told his audience that he had read on one of the tablets, a flood story very similar to that recorded in the book of Genesis.[2] Smith published his work in 1872 as well.[3]

This information caused a great stir not only because of its similarity to the Genesis flood but also it is claimed to have been written in seventeenth century BC while Moses wrote the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) two hundred years later in fifteenth century BC. Bible critics gleefully claimed that the Gilgamesh account was the original and Genesis account was merely an adaption of it.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh may have been a king who ruled over the Mesopotamian city of Uruk at around 2,600 BC.[4] The epic is based on his search for eternal life. In the legend, Gilgamesh is 2/3 divine and 1/3 mortal. He has enormous intelligence and strength, but he oppresses his people. The people call on the gods and in particular, the sun god Anu, the chief god of the city, who in response, makes a wild man called Enkidu with enough strength to match Gilgamesh. Eventually the two fight, but neither can win. Their enmity becomes mutual respect, then devoted friendship.

The two new friends set off on adventures together, but eventually the gods kill Enkidu. Gilgamesh grievously mourns his friend and realises that he too must eventually die. However, he learns of one who became immortal; Utnapishtim, the survivor of a global flood. Gilgamesh travels across the sea to find Utnapishtim, who tells of his remarkable life.[5]

The Gilgamesh flood story [6]

The council of the gods decided to flood the whole earth to destroy mankind. But Ea, the god who made man, warned Utnapishtim, from Shuruppak, a city on the banks of the Euphrates, and told him to build an enormous boat:

‘O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu:

Tear down the house and build a boat!

Abandon wealth and seek living beings!

Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings!

Make all living beings go up into the boat.

The boat which you are to build,

its dimensions must measure equal to each other:

its length must correspond to its width.’

Utnapishtim obeyed:

‘One (whole) acre was her floor space, (660’ X 660’)

Ten dozen cubits the height of each of her walls,

Ten dozen cubits each edge of the square deck.

I laid out the shape of her sides and joined her together.

I provided her with six decks,

Dividing her (thus) into seven parts.’

Utnapishtim sealed his ark with pitch, took all the kinds of vertebrate animals, and his family members, plus some other humans. Shamash the sun god showered down loaves of bread and rained down wheat. Then the flood came, so fierce that:

‘The gods were frightened by the flood,

and retreated, ascending to the heaven of Anu.

The gods were cowering like dogs, crouching by the outer wall.

Ishtar shrieked like a woman in childbirth,

the sweet-voiced Mistress of the Gods wailed:

“The olden days have alas turned to clay,

because I said evil things in the Assembly of the Gods!

How could I say evil things in the Assembly of the Gods?

ordering a catastrophe to destroy my people!!

No sooner have I given birth to my dear people

than they fill the sea like so many fish!”

The gods—those of the Anunnaki—were weeping with her,

the gods humbly sat weeping, sobbing with grief,

their lips burning, parched with thirst.’

However, the flood was relatively short:

‘Six days and seven nights

came the wind and flood, the storm flattening the land.

When the seventh day arrived, the storm was pounding,

the flood was a war—struggling with itself like a woman

writhing (in labor).’

Then the ark lodged on Mt Nisir (or Nimush), almost 500 km (300 miles) from Mt Ararat. Utnapishtim sent out a dove then a swallow, but neither could find land, so returned. Then he sent out a raven, which didn’t return. So he released the animals and sacrificed a sheep. This was not too soon, because the poor gods were starving:

‘The gods smelled the savor,

the gods smelled the sweet savor,

and collected like flies over a (sheep) sacrifice.’

Then Enlil saw the ark and was enraged that some humans had survived. But Ea sternly rebuked Enlil for overkill in bringing the flood. Whereupon Enlil granted immortality to Utnapishtim and his wife, and sent them to live far away, at the Mouth of the Rivers.

Here is where Gilgamesh found him, and heard the remarkable story. First Utnapishtim tested Gilgamesh’s worthiness for immortality by challenging him to stay awake for 7 nights. But Gilgamesh was too exhausted and quickly fell asleep. Utnapishtim asked his wife to bake a loaf of bread and place it by Gilgamesh every day he slept. When Gilgamesh awoke, he thought he had just been asleep for a moment. But Utnapishtim showed Gilgamesh the loaves at different stages of aging, showing that he had been asleep for days.

Gilgamesh once more lamented about his inevitable death, and Utnapishtim took pity on him. So he revealed where he could find a plant of immortality. This was a thorny plant in the domain of Apsu, the god of the subterranean sweet water. Gilgamesh opened a conduit to the Apsu, tied heavy stones to his ankle, sunk deep down, and grabbed the plant. Although the plant pricked him, he cut off the stones, and rose.

Unfortunately, on the return journey, Gilgamesh stopped at a cool spring to bathe, and a snake carried off the plant. Gilgamesh wept bitterly, because he could not return to the underground waters.

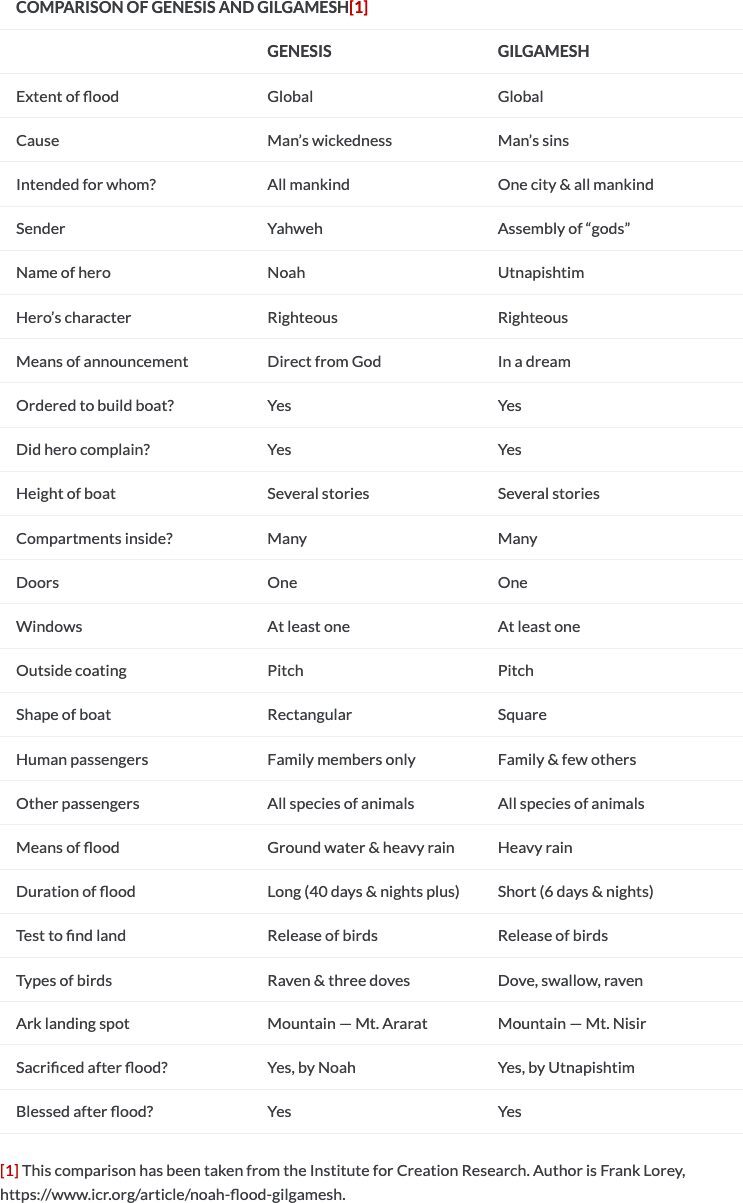

A comparison of the two flood accounts

The Gilgamesh Epic is clearly mythology. But there are many similarities with the Genesis flood as shown. This can only confirm a common origin. To add further weight to the idea of a common origin, other ancient flood stories have been found.

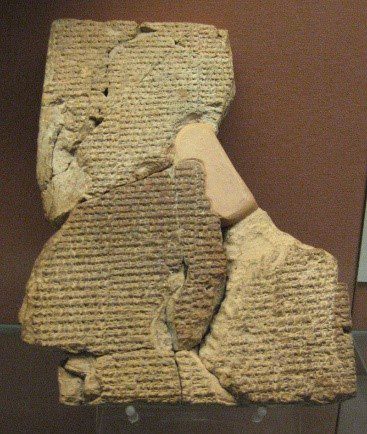

The Ziusudra Epic

The Ziusudra Epic

During the years of 1893 to 1896, archaeologist Arno People uncovered another flood story from a single fragmentary tablet written in Sumerian cuneiform from about 1600 BC. The narrative records the god Enki directing Ziusudra to build a large boat, followed by a missing section which in turn, was followed by a description of the flood. A seven-day storm tosses a huge boat, cubic in its dimensions, about on the water until the Sun (Utu) appears and the hero Ziusudra worships and offers an animal sacrifice to the gods.[7]

The Atrahasis Epic

This is another Mesopotamian flood story written on three broken tablets and also discovered by Austen Henry Layard in 1872 and translated by George Smith in 1876.

This is another Mesopotamian flood story written on three broken tablets and also discovered by Austen Henry Layard in 1872 and translated by George Smith in 1876.

This epic begins with the creation of mankind because the labour class gods are fed up with the heavy tasks imposed upon them by the management class gods, and they make much ‘noise’ especially against the chief god, Enlil. As a result, the mother goddess Mami and the magician god Enki create procreating people as a substitute for the labouring gods. The people multiply so much in 1200 years that they made a great ‘noise’ to the annoyance of Enlil. Enlil tries to exterminate them first by a famine, then 1200 years later by a drought, and finally, yet another 1200 years later, by the flood. Three times Enlil’s plans are foiled by Enki and his faithful worshipper Atrahasis. Now the thrice failing and furious Enlil convenes a divine assembly where a post flood compromise is reached among the gods to limit the expanding population.[8]

Other flood stories

Flood stories are ubiquitous amongst ancient civilizations. Almost all civilizations have a flood story as a legend or folklore in their culture. Evolutionary geologist Robert Schoch wrote:

Noah is but one tale in a worldwide collection of at least 500 flood myths, which are the most widespread of all ancient myths and therefore can be considered among the oldest.[9]

These flood stories are remarkably similar. James Perloff noted:

In 95 percent of more than 200 flood legends, the flood was worldwide; in 88 percent, a certain family was favored; in 70 percent, survival was by means of a boat; in 67 percent, animals were also saved; in 66 percent, the flood was due to the wickedness of man; in 66 percent, the survivors had been forewarned; in 57 percent, they ended up on a mountain; in 35 percent, birds were sent out from the boat; and in 9 percent, exactly eight people were spared.[10]

Conclusion

In comparing ancient flood stories, one aspect stands out; they are clearly myths involving gods who are weak, vengeful, emotional and the accounts are physically impossible with the whole earth flooded in seven days by only rain and the lifesaving boat is a perfect cube and as such, would be inherently unstable. The Genesis account is detailed (the people on board, number and types of animals, the length of the time it rained, the dimensions of the ark and its construction, etc.), it is descriptive (fountains of the deep broke open, the whole world covered with water) and purposeful (divine judgment on a very wicked people). It makes more sense to believe that Genesis was the original, the Gilgamesh Epic and the others, which lack the detail of the Genesis account, arose from and are a distortion of the original.

Even thought Moses wrote Genesis about 200 years after the Gilgamesh Epic, the scriptures were written as the incidents happened or close to them. The Flood about 3,500 BC. Genesis 5:1 states: This is the written account of Adam’s line. Adam’s line goes right through to Noah and the flood. Importantly, after the flood, Noah’s three sons and their wives started to re-populate the world and of course, they would have taken the account of the flood with them and this would be the reason for it being in all the history of all people groups.

John C Whitcomb makes the point: The Genesis account was kept pure and accurate throughout the centuries by the providence of God until it was finally compiled, edited, and written down by Moses.

Note, all images are credited to: Wikimedia commons

[1]https://www.britannica.com/topic/Epic-of-Gilgamesh.[2] David E Graves, The Archaeology of the Old Testament, Electronic Christian Media, Canada,2019, pages 58-60.

[3] George E Smith, The Chaldean Account of the Deluge, Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, 2, 1872, pages 213-234.

[4] Randall Price, The Stones Cry Out, harvest House Publishers, Oregon, 1997, page63.

[5] Jonathan Sarfati, Creation, September 2006,

[6] This account of the Gilgamesh flood story is taken from Jonathan Sarfati’s article above.

[7] David E Graves, The Archaeology of the Old Testament, Electronic Christian Media, Canada,2019, pages 58-60.

[8] Ibid.

[9] R. M. Schoch, Voyages of the Pyramid Builders, Jeremy P Parcher/Putnam, New York, 2003, page 249.

[10] J. Perloff, Tornado in a Junkyard: The Relentless Myth of Darwinism, Refuge Books, 1999, page 45.