Introduction

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah[1]

The establishment of a Jewish community on Elephantine Island.

There are no external sources on the history of the Elephantine community. However, the reason for the establishment of a Jewish settlement is given by Prof. Bezalel Porten, who wrote in the May-June 1995 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review:

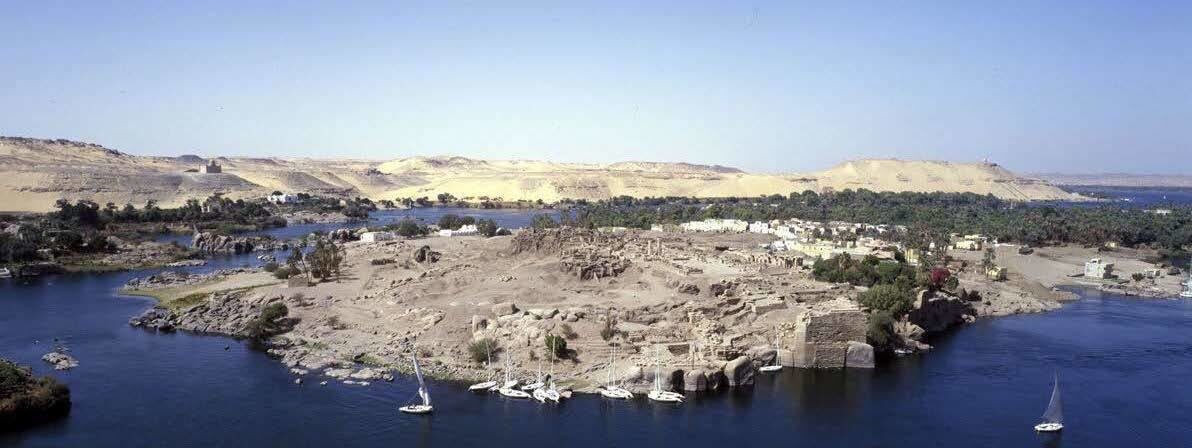

The Jewish community at Elephantine was probably founded as a military installation in about 650 b.c.e. during Manasseh’s reign. A fair implication from the historical documents, including the Bible, is that Manasseh sent a contingent of Jewish soldiers to assist Pharaoh Psammetichus I (664–610 b.c.e.) in his Nubian campaign and to join Psammetichus in throwing off the yoke of Assyria, then the world superpower. Egypt gained independence, but Manasseh’s revolt [against Assyria] failed; the Jewish soldiers, however, remained in Egypt.

Elephantine island on the Nile river near Aswan. Image credit: British Museum.

The discovery

The following account of the discovery of the Elephantine papyri is a condensed version of that of Bezalel Porten’s article; Did the Ark Stop at Elephantine? Biblical Archaeological Review, May/June, 1995.

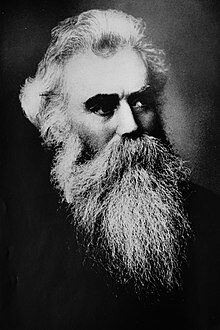

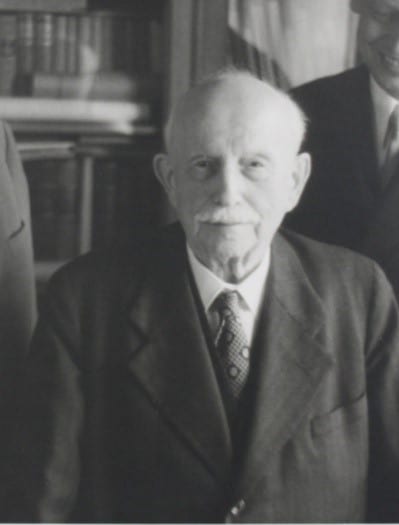

Charles Edwin Wilbour, an American journalist (pictured, Credit: Wikipedia commons) managed the New York Transcript, a major daily. In early 1893, he acquired some papyri from “3 separate women” at different times, during one of his trips to Egypt, according to his notebook entries for January and February of that year. Also included in the cache were fragments in an envelope on which he wrote, “Is not this authentic Phenician?” Wilbour showed the fragments to a distinguished Bible scholar, the Reverend A. H. Sayce, who had often travelled with him. Sayce correctly identified the pieces as Aramaic. Wilbour died in 1896 without having done anything with the hoard he had purchased from the “3 separate women.” After his death, his papyrus collection was shipped back to the United States in a trunk, along with his other finds. That trunk rested in a New York warehouse until the death of his daughter Theodora in 1947, and then it went to the Egyptian Department of the Brooklyn Museum. Only at that time, after the finds had lain unexamined for more than 50 years, did scholars learn that Wilbour had acquired the first Elephantine papyri.

Charles Edwin Wilbour, an American journalist (pictured, Credit: Wikipedia commons) managed the New York Transcript, a major daily. In early 1893, he acquired some papyri from “3 separate women” at different times, during one of his trips to Egypt, according to his notebook entries for January and February of that year. Also included in the cache were fragments in an envelope on which he wrote, “Is not this authentic Phenician?” Wilbour showed the fragments to a distinguished Bible scholar, the Reverend A. H. Sayce, who had often travelled with him. Sayce correctly identified the pieces as Aramaic. Wilbour died in 1896 without having done anything with the hoard he had purchased from the “3 separate women.” After his death, his papyrus collection was shipped back to the United States in a trunk, along with his other finds. That trunk rested in a New York warehouse until the death of his daughter Theodora in 1947, and then it went to the Egyptian Department of the Brooklyn Museum. Only at that time, after the finds had lain unexamined for more than 50 years, did scholars learn that Wilbour had acquired the first Elephantine papyri.

The next acquisition of an Elephantine papyrus was made by Sayce himself. While in Elephantine in early 1901, he was led to an ancient mound where some natives were digging. Sayce could see some papyrus fragments and ostraca (writings on pieces of pottery) which he proceeded to “rescue” from what he felt would have been certain oblivion. Upon his return to Oxford, he presented them to the Bodleian Library. They turned out to be three rolls that actually constituted a single Aramaic papyrus. This manuscript was published in 1903 by Sir Arthur Ernest Cowley, who characterized it as the longest and most continuous text of the kind hitherto published. It was a loan contract involving at least one Jew, dating to the fifth century BC.

The great acquisition however, was made in 1904 when two British philanthropists, Lady William Cecil and Mr. (later Sir) Robert Ludwig Mond, who separately acquired a total of 10 rolls. Lady Cecil and Mond had intended to ship the documents to a British institution, but the view of Howard Carter of Tutankhamen’s tomb fame, prevailed upon them to turn the texts over to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. One papyrus, however, did find its way into the Bodleian Library at Oxford. The Cecil-Mond papyri were published in 1906 by Sayce and Cowley.

In 1904 natives showed the findspot on Elephantine to Otto Rubensohn (1867- 1964 pictured) of the Königlichen (today Staatlichen) Museen in Berlin. Rubensohn soon organized an archaeological expedition to the site. There, on New Year’s Day 1907, he uncovered, just below the surface, three major documents relating to a Jewish temple at Elephantine. The texts were promptly forwarded to Berlin, where they were unrolled by the master conservator Hugo Ibscher and their contents promptly published by Eduard Sachau. Rubensohn and his colleague and successor Friedrich Zucker then went on to discover many more Aramaic papyri at the site, including 19 letters, 18 contracts, nine lists and accounts, a copy of the Behistun inscription of Darius the Great (522–486 BC), a 14-column work of ethical and wisdom literature known as Words of Ahiqar, as well as numerous fragments and inscriptions on potsherds, wood and stone. The whole collection was published in 1911.

soon organized an archaeological expedition to the site. There, on New Year’s Day 1907, he uncovered, just below the surface, three major documents relating to a Jewish temple at Elephantine. The texts were promptly forwarded to Berlin, where they were unrolled by the master conservator Hugo Ibscher and their contents promptly published by Eduard Sachau. Rubensohn and his colleague and successor Friedrich Zucker then went on to discover many more Aramaic papyri at the site, including 19 letters, 18 contracts, nine lists and accounts, a copy of the Behistun inscription of Darius the Great (522–486 BC), a 14-column work of ethical and wisdom literature known as Words of Ahiqar, as well as numerous fragments and inscriptions on potsherds, wood and stone. The whole collection was published in 1911.

The significance of the discovery

The people

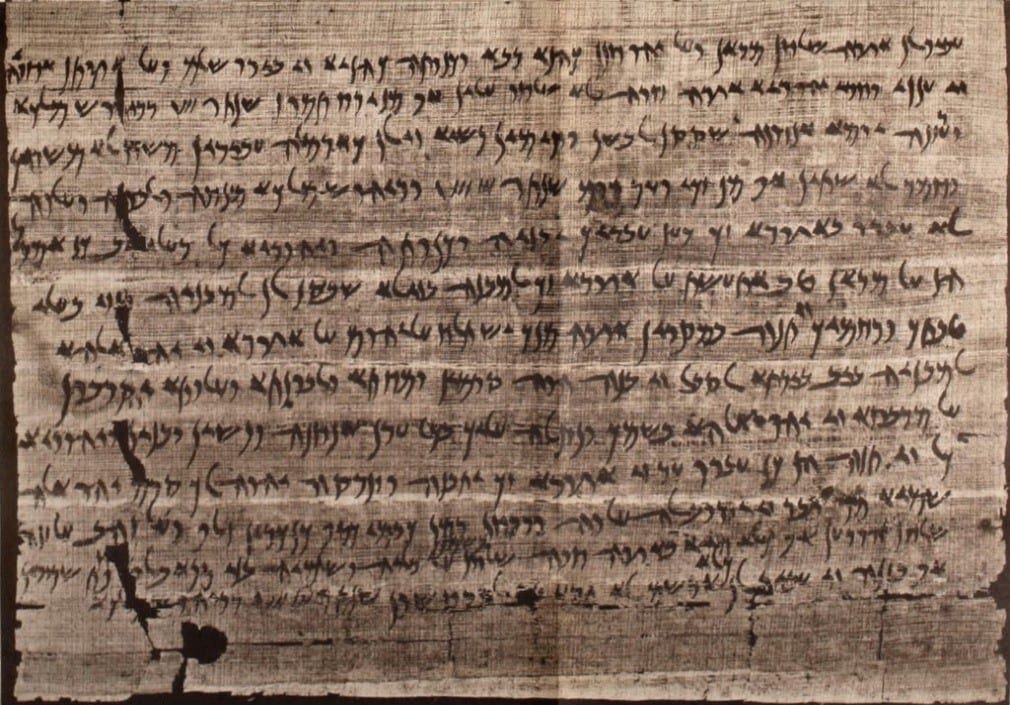

One papyrus letter caused particular excitement, it was unearthed in 1909, contains 30 lines written in ink of Aramaic text and dating to circa 407 BC. It is known as Elephantine Papyrus No. 30 (pictured), this document contains proof of two biblical figures and the positions they held; Jehohanan the high priest and Samaria’s governor, Sanballat the Horonite.

Papyrus No 30 states in part:

To Bagohi governor of Judah,[2] [from] the priests who are in Elephantine the fortress. [W]e sent a letter [to] our lord, and to Jehohanan the high priest and his colleagues the priests who are in Jerusalem, and to Ostanes brother of Anani and the nobles of the Jews.” Jehohanan is a longer version of the name “Johanan,” son of Eliashib the high priest, who served during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah. (This same Johanan is mentioned in Ezra 10:6 and Nehemiah 12:22-23.) Toward the end of the papyrus, it reads: Moreover, all these things in a letter we sent in our name to Delaiah and Shelemiah, sons of Sanballat, governor of Samaria. This Sanballat the Horonite, governor of Samaria, is mentioned numerous times (2:10, 19; 4:1; 6:1-2,5,12,14; 13:28) throughout the book of Nehemiah.[3]

The language

The biblical passages written in Aramaic are Ezra 4:8-6:18 and 7:12-26. Critical scholars once considered the Aramaic portions of Ezra spurious because the style appeared too recent to fit the traditional date. These considerations led some to date the books of 1 and 2 Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah as late as the third century BC.[4] The Elephantine Papyri show conclusively, however, that the Aramaic of Ezra was in use during the fifth century BC.

Conclusion

Again and again archaeology has confirmed the accuracy of the Bible. On this occasion, the Elephantine papyri authenticated the books of Ezra and Nehemiah by the names of prominent people; Jehohanan the high priest in both Ezra and Nehemiah and Sanballat, governor of Samaria in Nehemiah. As well, the Aramaic language used in the book of Ezra, was recorded on a papyrus letter to Bagohi governor of Judah. Bagohi has been mentioned as being the govenor of Judea by the Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities. 11:297–301).

References

[1] Although the opening sentence of Nehemiah state: The words of Nehemiah son of Hacaliah, indicate that Ezra and Nehemiah were two separate books, they were combined as one in the earliest Hebrew manuscripts. Josepheus (AD 37-100) the Jewish historian, and the Jewish Talmud refer to the book of Ezra and not to a separate book of Nehemiah. The oldest manuscripts of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament) also treat Ezra and Nehemiah as one book.Origen (AD 185-253) is the first writer known to distinguish between the two books, which he called I Ezra and II Ezra. In translating the Latin Vulgate (AD 390-405), Jerome called Nehemiah, the second book of Esdrae (Ezra). The English translations of Wycliffe (1382) and Coverdale (1535) also called Ezra “I Esdras” and Nehemiah “II Esdras.” The same separation first appeared in a Hebrew manuscript in 1448.

[2] Bagohi (Gr. Βαγώας), governor of the Persian satrapy Yehud (Judea) in the time of Darius II and Artaxerxes II. https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/bagohi.

[3] Watch Jerusalem, https://watchjerusalem.co.il/671-elephantine-papyrus-proving-the-book-of-nehemiah.

[4] http://www.truthmagazine.com/archives/volume45/V4501040109.htm. Citing Robert H. Phifer, Introduction to the Old Testament. Rev. ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969.