Their beginning

Initially, the great majority of Christians lived with their families and went to work six days a week. By AD 320, however, many hermit Christians existed out of sight and their numbers were increasing. Isolated corners of Syria attracted them; deserted Egyptian villages close to the Nile were another haven. After a time, however, many could not stand the isolation; they felt acutely the onset of boredom and were prey to robbers and thugs. So, they entered communities called monasteries, were known as monks and lived there permanently. In a similar fashion, women gathered together in convents, but this happened later. Some of the hundreds of monasteries are shown below.[1]

Pachomius’ Rules

During the fourth century Egyptian hermit Pachomius devised a set of strict rules for monks to live by. He thought that, since the outside world was a dangerous infection, the monks inside his walls should hear as little news as possible from the city of Alexandria. Rule 60, as approved by Pachomius, instructed the monks to discuss no worldly matters. On Sunday, when they washed their clothes, they did it in silence. Those who task it was to bake the daily bread were not allowed the pleasure of private chatter but instead recite verses from the Bible. Other daily tasks, such as soaking reeds for the making of twine for ropes and preparing palm leaves for baskets, were presumably done in silence. In the hall where nearly all dined at noon, silence reigned. Sign language was used so that food could be passed along the table.

Further; hospitality was generously dispersed to pilgrims and to journeying monks from other monasteries. Pachomius recognised that female travellers were capable of upsetting the contentment of the monastery. If they arrived at nightfall, however, it would surely be mean to drive them away. Pachomius discussed this dilemma: as women, they should be treated with even more honour than the male visitors, but also with more ‘diligence’. Accordingly, they were placed in a separate guesthouse, enclosed by a wall or fence.[2]

Western Europe had been slow to adopt the idea, and its first monastery was not opened until AD 361, near Poitiers in present day France. This was founded by Martin, a former soldier, it was such a success that he became the Bishop of Tours in 372. Celebrated in his day, his name was handed down to the first Protestant, Martin Luther, more than eleven hundred years later.

Benedictine’s Rules.

The most influential set of rules for monks to follow, were written by Benedict of Nursia, abbot of the great Italian monastery of Monte Cassino in about 575. Under the Benedictine Rule. Men lived together in community pledging total obedience to the abbot, or head of the monastery who were elected by the monks. The monk’s waking hours were divided between work and prayer. Many monasteries supported themselves by farming, so most of the monks spent their working hours in the fields. Others were assigned to take care of the daily running of the monastery working as cooks, porters or bell ringers. In some monasteries, monks made wine. Whatever the monks did, they did it for the glory of God, and they considered their work a form of prayer. In his Rule, Benedict put aside several hours a day for sacred reading, using the method known a lectio divina (divine reading). This is a form of contemplative prayer in which the monk would slowly and carefully read a passage from the Bible or some other Christian text and then concentrate on its meaning for his life.[3]

Monasteries copied, stored and protected scripture

Because Bible reading was so much a part of a monk’s life, documents became worn and needed to be replaced; some monks were assigned to coping manuscripts for use in the monastery. To do this they had to spend long hours in preparing parchment pages and their own pens and ink. As a result, from the earliest of times the sacred scriptures were stored in the monastery and were kept under its protection.

During the passing of the centuries, cities, kingdoms and empires rose and fell. Invaders such as the Vandals, Vikings, Barbarians, Mongols, Muslims, etc meant that no repository of manuscripts and books were safe, but monasteries were, because they were no threat to any invading power and in many cases, they were built in isolated places and were difficult to reach.

The destruction of libraries

Libraries have been deliberately or accidentally destroyed or badly damaged for the past 2,500 years. Sometimes a library is purposely destroyed to eradicate a people’s history as a form of cultural cleansing. Wikipedia lists 88 significant libraries that have been destroyed right across the world.[4] All the information that they contained has been lost for all time.

Two examples of this loss of written information are the loss of the ancient world’s single greatest archive of knowledge, the Library of Alexandria. This happened when Caesar, set ships in the harbour on fire in order to protect his army, but the fire spread on to the land and incinerated the library among many other buildings. The other example is the destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem in AD 70 by the Roman army. The fire destroyed all written information it contained.

The Arnstein Bible: a giant monastic Bible

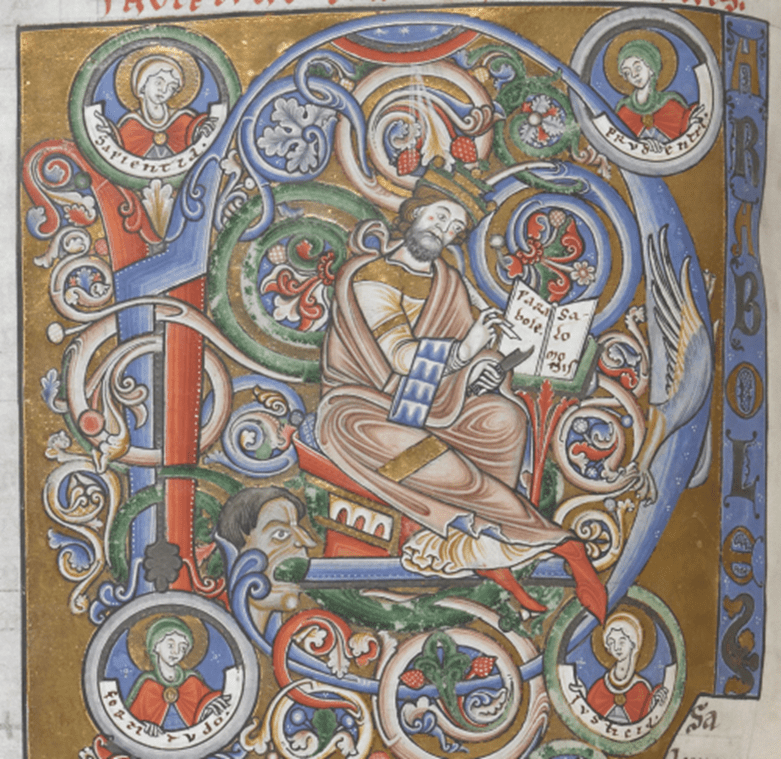

The Arnstein Bible is one of several Giant Bibles that originated in monasteries in Europe and Britain. Their production was confined to the twelfth century. They are very large, and highly and elaborately decorated. They provide an insight into the printing power, competence and diligence of the monks in these monasteries. The Arnstein Bible, which measures, 545 x 375 mm (21.5 x 14.8 inches) and written entirely in Latin on parchment, was produced at the Premonstratensian abbey of St Mary and St Nicholas, Arnstein, in Germany (pictured. Photo credit Wilkimedia commons). This abbey was founded in 1139 by Ludwig III. The Arnstein Bible was compiled in two volumes by Lunandus, a monk of Arnstein Abbey, in 1172 or 1173. It consists of Genesis to Malachi for volume 1 and Job to Revelation in volume 2 with large illuminated and decorated initials at the beginning of each of the biblical books. An indication that this Bible is a great monastic book is the inclusion of not one, but rather three of Jerome’s translations of the book of Psalms, arranged in three parallel columns, each of 80 mm width. This allowed the reader to study the variant Psalm texts across the page. The image shows the initials for the beginning of Psalm 101, ‘D’(omine) features different figures in the bowl of the letter: Christ blessing, the Virgin and Child, and a bishop.

The Arnstein Bible is one of several Giant Bibles that originated in monasteries in Europe and Britain. Their production was confined to the twelfth century. They are very large, and highly and elaborately decorated. They provide an insight into the printing power, competence and diligence of the monks in these monasteries. The Arnstein Bible, which measures, 545 x 375 mm (21.5 x 14.8 inches) and written entirely in Latin on parchment, was produced at the Premonstratensian abbey of St Mary and St Nicholas, Arnstein, in Germany (pictured. Photo credit Wilkimedia commons). This abbey was founded in 1139 by Ludwig III. The Arnstein Bible was compiled in two volumes by Lunandus, a monk of Arnstein Abbey, in 1172 or 1173. It consists of Genesis to Malachi for volume 1 and Job to Revelation in volume 2 with large illuminated and decorated initials at the beginning of each of the biblical books. An indication that this Bible is a great monastic book is the inclusion of not one, but rather three of Jerome’s translations of the book of Psalms, arranged in three parallel columns, each of 80 mm width. This allowed the reader to study the variant Psalm texts across the page. The image shows the initials for the beginning of Psalm 101, ‘D’(omine) features different figures in the bowl of the letter: Christ blessing, the Virgin and Child, and a bishop.

As mentioned, an example of the Bible’s detailed and ornate calligraphy is at the start of each book. The one shown, is at the commencement of Proverbs with a depiction of Solomon writing.

As mentioned, an example of the Bible’s detailed and ornate calligraphy is at the start of each book. The one shown, is at the commencement of Proverbs with a depiction of Solomon writing.

The Arnstein Bible was sold to Robert Harley on 16 January 1720/21 and his daughter, Margaret Cavendish Bentinck and his wife, the duchess of Portland, sold it 1753, to the nation of Britain for £10,000 and it now resides in the British Library.[5] The library has produced a facsimile of the Giant Bibles in book form titled, The Art of the Bible and is available from many bookstores.[6]

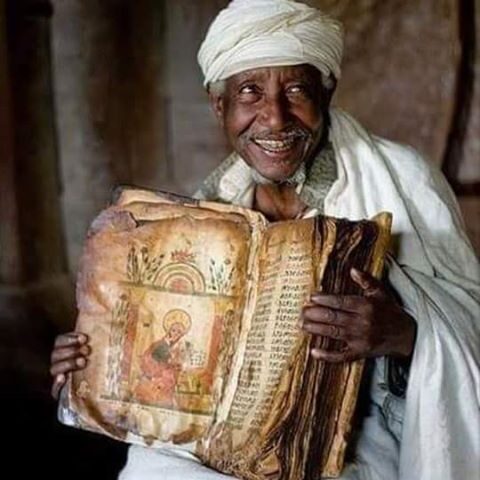

Abba Garima Monastery

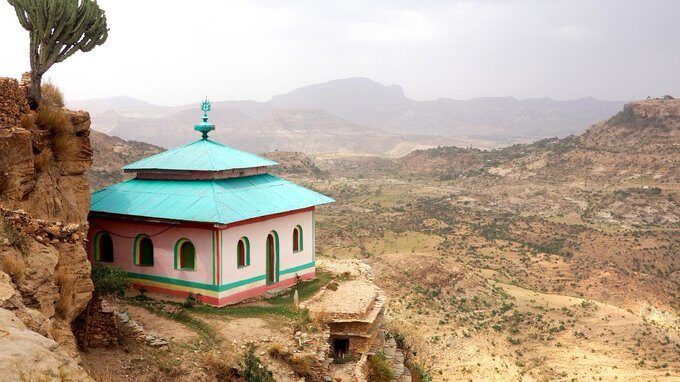

Abba Garima Monastery is an Ethiopian Orthodox church, located in the Mehakelegnaw Zone of the northern Tigray Region in Ethiopia. It was established in the sixth century by Abba Garima, and built by King Gabra Masqal (also Gebre Meskel). The monastery became known for its early manuscripts and its copy of the gospels.

Abba Garima Monastery is an Ethiopian Orthodox church, located in the Mehakelegnaw Zone of the northern Tigray Region in Ethiopia. It was established in the sixth century by Abba Garima, and built by King Gabra Masqal (also Gebre Meskel). The monastery became known for its early manuscripts and its copy of the gospels.

Researchers have discovered ancient and highly illustrated biblical books in the monastery, revealing a rich tradition of Christianity in the West African country. The books are called the Garima Gospels, named after a monk Abbu Garima, who is credited with writing them and doing much of the illustration work. They were translated from Greek and are the earliest recorded translation of the four gospels into Ge’ez, the language of the Ethiopian church. They are written on vellum.

Abbu Garima came to Ethiopia in AD 494 from Constantinople. Recent radiocarbon dating of the two books, carried out at Oxford University suggested a date between AD 330 and AD 650 for their creation, supporting the contention that the gospels were actually created by Abba Garima. If this is true, then they are possibly the earliest surviving illuminated Christian manuscripts.[7]

Abbu Garima came to Ethiopia in AD 494 from Constantinople. Recent radiocarbon dating of the two books, carried out at Oxford University suggested a date between AD 330 and AD 650 for their creation, supporting the contention that the gospels were actually created by Abba Garima. If this is true, then they are possibly the earliest surviving illuminated Christian manuscripts.[7]

The Garima Gospels have been kept high and dry, which has helped preserve them all these years and they are kept in the dark, so the colors look fresh.

The finding is a reminder of Ethiopia’s deep connection with Christianity. Ethiopia was one of the first African countries that received the gospel. Acts 8:27 mentions an Ethiopian man who encountered Philip and eventually went back to Ethiopia to share the gospel.

Photo credit: ancient-origine.com.

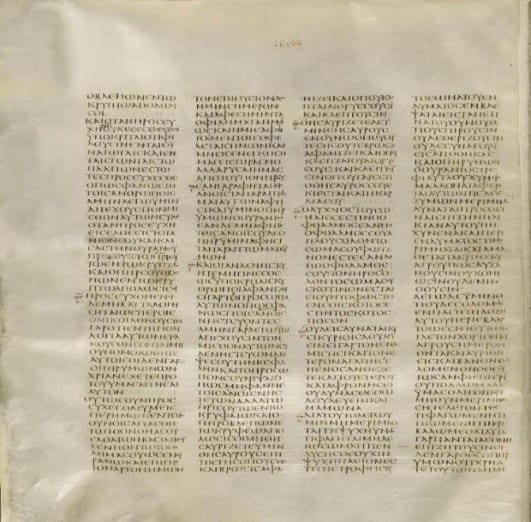

Codex Sinaiticus

Constantin Tischendorf was born, in Saxony Germany in 1815. He began his scholarly career at the University of Leipzig in 1834 and took a special interest in the early writings of the New Testament. This gave him a desire to use the oldest manuscripts in order to compile the text of the New Testament as close to the original as possible. He came to realise that:

The literary treasures that I have sought to explore have been drawn in most cases from the convents of the east, where for ages, the pens of industrious monks have copied the sacred writings, and collected manuscripts of all kinds. It therefore occurred to me whether it was not probable that in some recess of Greek or Coptic, Syrian or Armenian monasteries, there might be some precious manuscripts slumbering for ages in dust and darkness.[8]

So, in true Raiders of the Lost Ark fashion, he set off and in May 1844 at the age of 29, he came across the Convent of St Catherine at the foot of Mt Sinai (pictured); the oldest continually inhabited monastery in the world. It was constructed in 565. It has no doors and Tischendorf had to be lifted up to a window high off the ground to gain entrance. It was here that he made a great manuscript find; A whole New Testament written on parchment and in the original Greek uncial letters (capital letters) and in codex form (book form as opposed to scroll form). It has been dated paleographically to the mid-4th century. To put this into context, the 27 books of the New Testament was only settled on by the councils at Hippo in 393 and at Carthage in 397. This book became known as Codex Sinaiticus. It is still the oldest copy of the New Testament in existence and considered to be the most valued. A page is shown. For my blog on Tischendorf’s discovery, click here https://www.adefenceofthebible.com/2017/03/14/tischendorfs-great-manuscript-find.

So, in true Raiders of the Lost Ark fashion, he set off and in May 1844 at the age of 29, he came across the Convent of St Catherine at the foot of Mt Sinai (pictured); the oldest continually inhabited monastery in the world. It was constructed in 565. It has no doors and Tischendorf had to be lifted up to a window high off the ground to gain entrance. It was here that he made a great manuscript find; A whole New Testament written on parchment and in the original Greek uncial letters (capital letters) and in codex form (book form as opposed to scroll form). It has been dated paleographically to the mid-4th century. To put this into context, the 27 books of the New Testament was only settled on by the councils at Hippo in 393 and at Carthage in 397. This book became known as Codex Sinaiticus. It is still the oldest copy of the New Testament in existence and considered to be the most valued. A page is shown. For my blog on Tischendorf’s discovery, click here https://www.adefenceofthebible.com/2017/03/14/tischendorfs-great-manuscript-find.

Summary

Monasteries became places where Christian men, and later women in convents, could live a life of dedication to God by concentrating on His written word in almost complete silence. Also, they were places of safety and were free from worldly influences.

While wars raged across the world and libraries were destroyed, God kept the Bible in monasteries where they were protected, duplicated and even beautified with ornate drawings in such a way as to dignify the book. As well, these enhancements became important material evidence of the status and wealth of the monasteries that commissioned and produced these Bibles. It shows as well, the centrality the Bible held in monastic life.

[1] Geoffrey Blainey, A Short Story of Christianity, Published by the Penguin Group, 2011, page 92.[2] Geoffrey Blainey, A Short Story of Christianity, Published by the Penguin Group, 2011, page 93-94.

[3] Stephen M Miller and Robert V Huber, The Bible: A History the Making and Impact of the Bible, Lion Publishing plc, Book, 2003, page 122.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_destroyed_libraries.

[5] http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Harley_MS_2798.

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C3fORUQL30g.

[7] https://minimamedievaliablog.wordpress.com/2017/03/17/hidden-gospels-oxford.

[8] Echoes of Jesus does the New Testament Reflect What He Said? Jonathan Clerke, Icefire Publishing, 2014, pages 133-134; citing: C. Tischendorf, Codex Sinaiticus: The Ancient Biblical Manuscript Now in the British Museum: Tischendorf’s Story and Argument Related by Himself. English trans., The Lutterworth Press, London, 1934, pages 16-17.