Introduction

In Old Testament times, letters were written on papyrus paper (abundant, inexpensive, but not long lasting), parchment (animal skins, long lasting but expensive), clay tablets (inexpensive but cumbersome) or on broken pottery (readily available, easy to use and long lasting). Pieces of broken pottery with writing are known as ostraca (ostracon is singular). They are sometimes called potsherds. Thousands of ostraca have been unearthed throughout Judah, Samaria and Egypt and are often receipts, accounts and letters. In the case of the Lachish Letters, the handwriting is in Palaeo-Hebrew script, written in iron carbon ink.

Their discovery

In 1935 JL Starkey unearthed 18 ostraca in the gate tower of Lachish (Tell ed-Duweir) and discovered three more in 1938. The image below, is that of James L Starkey, head of the British expedition at the site of the entrance gate of the old city, pointing to where he found the Lachish Letters. His work came to an abrupt halt in 1938 when he was murdered on his way to the opening ceremony of the Palestine Archaeological Museum.

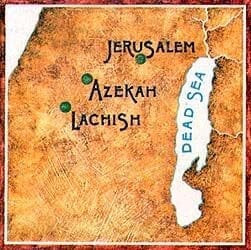

The more legible letters were published in 1938 by Harry Torczyner and they consist of hastily scribbled letters that record brief lists of names and correspondences between a Judean military outpost and the city of Lachish, 40 km (25 ml) south-west of Jerusalem. These were written immediately prior to the Babylonian invasion of Judea (589 to 588).[1]

The more legible letters were published in 1938 by Harry Torczyner and they consist of hastily scribbled letters that record brief lists of names and correspondences between a Judean military outpost and the city of Lachish, 40 km (25 ml) south-west of Jerusalem. These were written immediately prior to the Babylonian invasion of Judea (589 to 588).[1]

Some of the letters were written from the military outpost by a man named, Hoshaiah, to the commanding officer at Lachish named Ys’osh’s (Yaosh).[2] They depict exasperation as the lights were seen to go out at the nearby city of Azekah in the wake of the dreaded Babylonian army. Both Lachish and Azekah were cities on hills and they communicated by lighting beacons. In Letter 4, Hoshaiah writes:

Some of the letters were written from the military outpost by a man named, Hoshaiah, to the commanding officer at Lachish named Ys’osh’s (Yaosh).[2] They depict exasperation as the lights were seen to go out at the nearby city of Azekah in the wake of the dreaded Babylonian army. Both Lachish and Azekah were cities on hills and they communicated by lighting beacons. In Letter 4, Hoshaiah writes:

And let (my Lord) know that we are watching for the beacons of Lachish….we cannot see (the beacons from ) Azekah.

Hoshaiah assumes that since the beacons of Azekah no longer burn, the city has already fallen.[3]

Jeremiah’s records the situation so clearly:

While the army of the king of Babylon was fighting against Jerusalem and the other cities of Judah that were still holding out; Lachish and Azekah. These were the only fortified cities left in Judah.[4]

Jeremiah’s statement shows that Lachish and Azekah were the last cities to fall before the Babylonians took Jerusalem exactly as the Lachish letters reveal.

Randel Price writes: “Even the emotional pathos of the moment has been preserved for us. Though written in the customary language of polite formality, we can still feel Hoshaiah’s desperation when he writes;

May Yahweh cause my lord to hear news of peace, even now, even now!

News of peace, however, did not come, and the Babylonians marched right over Lachish and into Jerusalem, setting fire to the city when they captured it.” The event is recorded in 2 Kings 25:1-21 and Jeremiah 39:1-10.

News of peace, however, did not come, and the Babylonians marched right over Lachish and into Jerusalem, setting fire to the city when they captured it.” The event is recorded in 2 Kings 25:1-21 and Jeremiah 39:1-10.

In order to give some idea of their physical size and nature, A photograph of a researcher examining ostracon Lachish 4 (in hand) at the Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem, is included.[5]

Conclusion

We see once again, the people, places and events recorded in the Bible being confirmed by archaeology. Not only is the attack by Nebuchadnezzar’s army on Jerusalem recorded in 2 Kings 25:1-21 and Jeremiah 39:1-10, but so is the fact that Lachish and Azekah were the last two cities to fall before Nebuchadnezzar took Jerusalem.

The Bible contains within its pages, an account of real history.

[1] Joseph M Holden and Norman Geisler, The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible, Harvest House Publishers, Oregon, 2013, page 271. ` [2] Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lachish-letters. [3] 40 by 40 Forty Groundbreaking Articles from Forty Years of Biblical Archaeology Review, Volume Two, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2015, page 346. [4] Jeremiah 34:7. [5] pef.org.uk/blog/the-lachish-letters-in-jerusalem.

1 Comment. Leave new

Fascinating praise God!