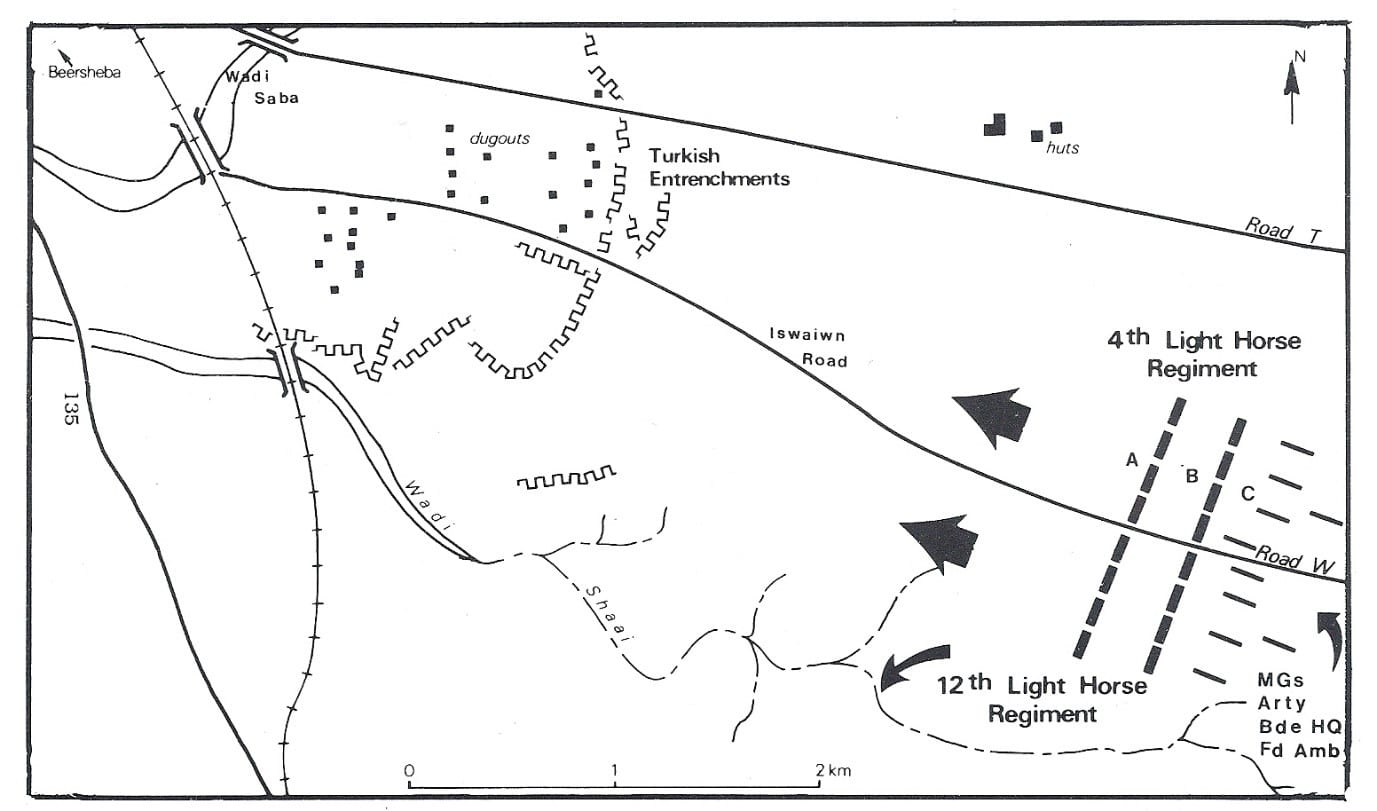

After the ANZACs had been withdrawn from the disaster which was Gallipoli. While the fighting that left the fields of northern France and Belgium drenched with blood was bogged down, British troops with their allies proceeded to take the Holy Land from the Ottoman Turks who had held it for 400 years. Progress was steady until it ground to a halt in the Sinai Desert, the Turks established a defensive line from Gaza across to Beersheba (Be’er Sheva) and two assaults on this line in March and April of 1917, failed, and resulted in 10,000 British casualties. The newly appointed General Allenby on assessing the situation, realised that a fresh attack was needed. However, they could only stay another 24 hours as their water supply was almost exhausted and Beersheba contained the only wells in the area. The previous night, Australian Lt-General Sir Harry Chauvel brought 20,000 of his mounted troops up 40 Km to within striking distance of Beersheba. Instructed by Allenby to capture Beersheba, Chaevel told Brigadier-General William Grant to mount a charge at the estimated 4,000 Turkish and German troops dug in there. Grant arranged 800 men comprising the 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Regiment to charge the enemy positions in two waves 300 to 500 metres apart and across a front of some 1100 metres. The charge was planned for 4.30 in the afternoon with the setting sun behind them. The charge started at a slow trot, but when within two km, the horses moved into a gallop. With the smell of water in their nostrils they could not be held back, for they had not drank for 48 hours. Their ranks held fast as the horses galloped five metres apart. They mounted the Turkish lines before the defenders could prepare themselves. Most of the fighting was hand to hand and by nightfall Beersheba was in allied hands. Of the 800 men who charged, 31 died, 36 were wounded and at least 70 horses died. Grant later told his troops that they had taken part in, “the greatest cavalry charge in the history of warfare.”

that left the fields of northern France and Belgium drenched with blood was bogged down, British troops with their allies proceeded to take the Holy Land from the Ottoman Turks who had held it for 400 years. Progress was steady until it ground to a halt in the Sinai Desert, the Turks established a defensive line from Gaza across to Beersheba (Be’er Sheva) and two assaults on this line in March and April of 1917, failed, and resulted in 10,000 British casualties. The newly appointed General Allenby on assessing the situation, realised that a fresh attack was needed. However, they could only stay another 24 hours as their water supply was almost exhausted and Beersheba contained the only wells in the area. The previous night, Australian Lt-General Sir Harry Chauvel brought 20,000 of his mounted troops up 40 Km to within striking distance of Beersheba. Instructed by Allenby to capture Beersheba, Chaevel told Brigadier-General William Grant to mount a charge at the estimated 4,000 Turkish and German troops dug in there. Grant arranged 800 men comprising the 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Regiment to charge the enemy positions in two waves 300 to 500 metres apart and across a front of some 1100 metres. The charge was planned for 4.30 in the afternoon with the setting sun behind them. The charge started at a slow trot, but when within two km, the horses moved into a gallop. With the smell of water in their nostrils they could not be held back, for they had not drank for 48 hours. Their ranks held fast as the horses galloped five metres apart. They mounted the Turkish lines before the defenders could prepare themselves. Most of the fighting was hand to hand and by nightfall Beersheba was in allied hands. Of the 800 men who charged, 31 died, 36 were wounded and at least 70 horses died. Grant later told his troops that they had taken part in, “the greatest cavalry charge in the history of warfare.”

This successful charge opened up the Holy Land as Gaza fell on November 7, followed by Jerusalem on December 9 and further fighting placed the Holy Land into British hands.

This successful charge opened up the Holy Land as Gaza fell on November 7, followed by Jerusalem on December 9 and further fighting placed the Holy Land into British hands.

The Balfour Declaration

On the same day as this successful charge, October 31, 1917, the British Government agreed to a request from their Foreign Secretary, Lord Arthur James Balfour, which was formalised in a letter to Lord Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild on November 2 and became known as the Balfour Declaration:

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

The declaration gave great hope to the Jewish people as Britain was a world power and would soon assume post-war control of Palestine. The dream of a modern Jewish state would not be realised until May 1948, but it started with the land coming under British control and British intention for it to revert back to Jewish hands, as God gave the land to the Children of Israel as an everlasting possession.[1]

Martin Luther was born in Eisleben in Germany in 1483 into a moderately wealthy family as his father was a successful miner and he wanted his son to study Law. However, Martin found Law and then Philosophy to be unfulfilling; he wanted to know more about God. On July 17, 1505, Luther entered St Augustine’s Monastery in Erfurt.

Martin Luther was born in Eisleben in Germany in 1483 into a moderately wealthy family as his father was a successful miner and he wanted his son to study Law. However, Martin found Law and then Philosophy to be unfulfilling; he wanted to know more about God. On July 17, 1505, Luther entered St Augustine’s Monastery in Erfurt.

In 1507 he was an ordained priest and one year later he entered the University of Wittenberg where he studied and obtain bachelor degrees and then a Doctor of Philosophy and later became a Professor of Theology. All the while Luther was haunted by his sinful nature and how he could become right with God. It was only through his study of the Bible and in particular, Ephesians 2:8-10 and Romans 1:16-17 which states:

I am not ashamed of the gospel because it is the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes………..”The righteous will live by faith.”

that Luther came to understand and stated that salvation was by grace alone through faith alone, in Christ alone. And this was in mark contrast to what was practised in the church, where salvation by works was taught. What particularly riled him was the practise by pope Leo X in the selling of indulgencies. That is people could pay money to have their deceased loved ones prayed to be delivered out of purgatory, a non-biblical place, into heaven. The pope used the money to build Saint Peter’s Basilica.

This all came to a head when Luther nailed his 95 theses to the church door of Wittenberg Castle on October 31, 1517. This was the practise at the time to initiate discussion on certain subjects and it appears that is all Luther was seeking. However, copies of Luther’s theses were made, the movable type printing press was invented about 60 years previously, and sent around the country and to the pope. In 1520, a bull of condemnation was issued by the pope and sent to Luther who burnt it. In the meantime, Luther expanded his condemnation of the church to include the doctrine of the Mass and the office of the pope.

In 1521 the Holy Roman empire convened a diet, or council at the town of Worms to address the problem of Martin Luther who was ordered to stand before it. After four months, the Emperor Charles V presented the final draft of the Edict of Worms on 25 May 1521, declaring Luther an outlaw, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest: “We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic.” It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. It permitted anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence.[2]

This painting of Martin Luther (1529) is by Lucas Cranach the Elder

This painting of Martin Luther (1529) is by Lucas Cranach the Elder

Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, hid Luther in Wartburg Castle, Eisenach for nearly one year. During this time, he translated the New Testament into German which was an enormous success selling 5,000 copies in two months.

The flame that Luther ignited at Wittenberg spread like wildfire throughout Europe and around the world as other preachers joined the cause and gave birth to what later became known as Protestantism. Luther died 18 February 1546 (aged 62) in Eisleben, Saxony.

[1] Genesis 12:7; 13:14, 15, 17; 15:7; 15:18.

[2] Jonathan Hill, The History of Christianity, Lion Hudson plc, 2007, pages 249-254; Alister McGrath, Christianity’s Dangerous Idea, Harper One, 2007.